Cash in the new post-crisis world and Climate change: testing the resilience of corporates’ creditworthiness to natural catastrophes: Difference between pages

imported>Jeeten.patel@thinkpublishing.co.uk No edit summary |

imported>Doug Williamson m (Categorise.) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

|subheaderstyle = | |subheaderstyle = | ||

|title = | |title = | ||

|above = | |above = Risk management | ||

|subheader = | |subheader = | ||

|subheader2 = | |subheader2 = | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

|headerstyle = background:#490024; color:#fff; padding:5px 0px; font-size:10pt; | |headerstyle = background:#490024; color:#fff; padding:5px 0px; font-size:10pt; | ||

|labelstyle = padding-top:7px; padding-bottom:5px | |labelstyle = padding-top:7px; padding-bottom:5px; | ||

|datastyle = padding-top:7px; padding-bottom:5px | |datastyle = padding-top:7px; padding-bottom:5px; | ||

|header1 = Authors | |header1 = Authors | ||

| label1 = | | label1 = | ||

| data1 = | | data1 = | ||

|header2 = | |header2 = | ||

| label2 = | | label2 =Miroslav Petkov | ||

| data2 = | | data2 =[http://www.standardandpoors.com/en_EU/web/guest/home Standard & Poor’s], London | ||

|header3 = | |||

| label3 =Michael Wilkins | |||

| data3 =[http://www.standardandpoors.com/en_EU/web/guest/home Standard & Poor’s], London | |||

|belowstyle = background:#ddf; | |belowstyle = background:#ddf; | ||

|below = | |below = | ||

}} | }} | ||

__TOC__ | |||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

While recent history shows that natural catastrophes may have not been a major rating factor on corporate credit quality in the past, their effect in the future may increase considerably if, as scientific evidence suggests, we experience more frequent and more extreme climatic events. If such extreme events were to occur, companies’ existing insurance and overall disaster risk management measures could, in the opinion of Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services, become considerably less effective. Therefore, we see improvements in companies’ disclosures about their exposure to natural catastrophes becoming more relevant to our ratings analysis. | |||

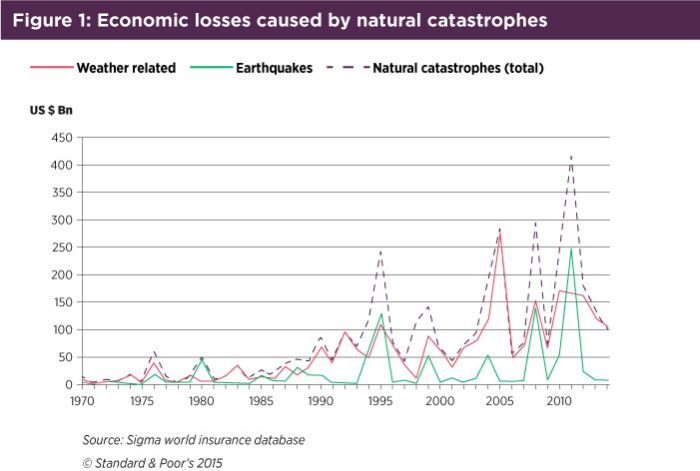

The economic cost of natural catastrophes has risen significantly over the past 10 years (see Figure 1 below). However, through a combination of existing preventive measures, most of the companies we rate have managed to mitigate the impact of such events on their corporate credit profiles. Nevertheless, with scientists predicting an increase in extreme climatic events, firms’ vulnerability to natural catastrophes is in our view likely to be sorely tested. | |||

===Overview=== | |||

* Generally, companies have so far managed to mitigate the effects of natural catastrophes through liquidity management, insurance protection, natural disaster risk management, and post-event recovery measures. | |||

* However, the more frequent and more extreme climatic events many scientists predict could adversely affect companies’ credit profiles in the future. | |||

* Greater disclosure of firms’ exposure to extreme natural catastrophes should, in our opinion, encourage them to bolster their resilience to these events and thereby aid transparency. | |||

[[File:Natural_loses_caused_by_natural_catastrophes.jpg|700px|center]] | |||

==Catastrophes seldom trigger rating actions – yet== | |||

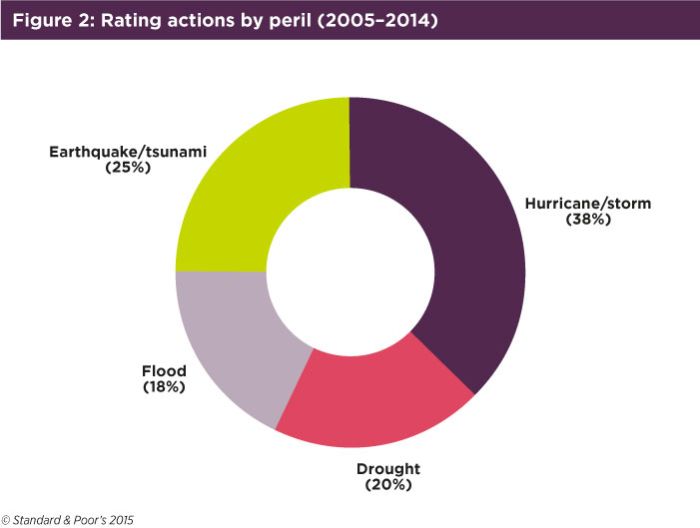

Although natural catastrophes can result in companies experiencing property losses and production and market disruptions, such events are not frequently a factor behind our negative rating actions. Since 2005, we have identified natural catastrophes (tropical storms, floods, droughts, and earthquakes) as the main or material contributing factor for at least 60 negative rating actions (comprising downgrades and outlook revisions). This compares with around 6,300 corporate credit downgrades on companies in total over that period. In addition, we revised our outlook on less than five companies to stable from positive as a result of natural catastrophes. Overall, we find that companies’ liquidity management, insurance protection, natural disaster risk management, and post-event recovery measures were adequate in mitigating the impact of natural catastrophes on their rating profiles during the period. | |||

[[File:Figure2_rating_actions_by_peril.jpg|700px|center]] | |||

== | ==Energy and consumer products sectors most at risk== | ||

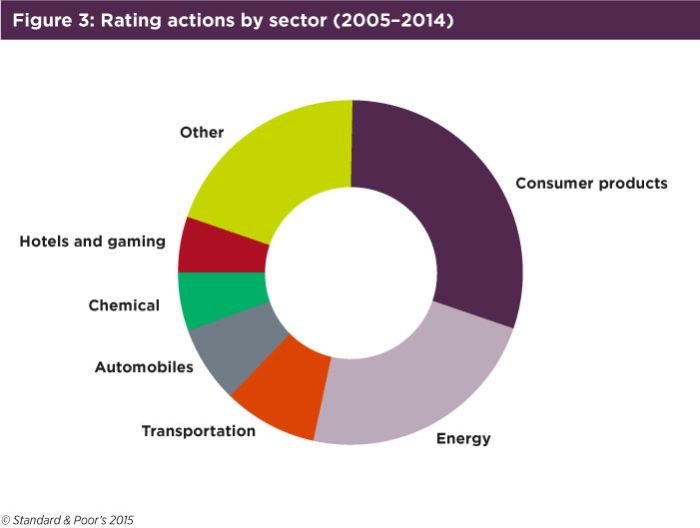

While our sample of negative rating actions is too small to draw robust statistical conclusions, our analysis provides insights into how and when natural catastrophes can affect companies’ creditworthiness. | |||

No sector is immune to the effects of natural catastrophes. However, the energy sector (through a direct impact on production and distribution facilities and market dislocation) and the consumer products sector (through supply chain and market disruptions) appear most exposed, together representing more than one half of the affected sample. This is about double the proportion of rated companies that make up each of those sectors. | |||

[[File:Figure3_Rating_actions_by_sector.jpg|700px|center]] | |||

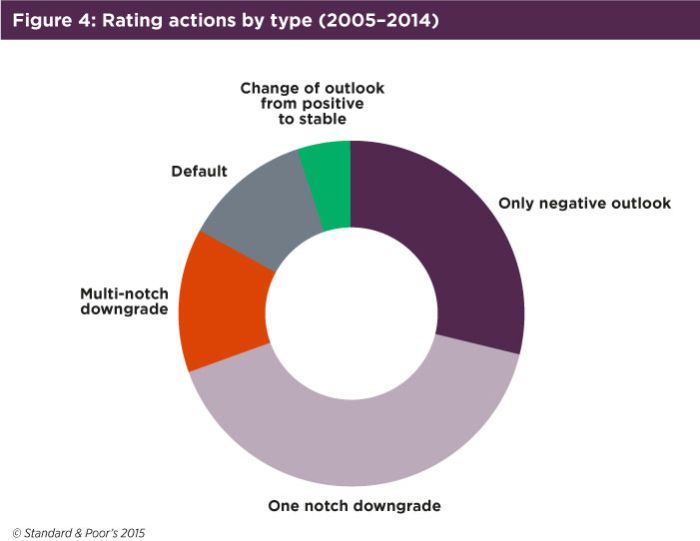

In around 40% of cases, natural catastrophes led to a one-notch downgrade. In a further 30%, we assigned a negative outlook that we subsequently resolved by affirming the rating. However, on average it took about 15 months for the credit profile of these latter companies to recover sufficiently for us to revise the outlook to ‘stable’. Across the rest of the sample, natural catastrophes contributed to multi-notch downgrades, and in about 10% of cases to default. Overall, this affected nearly twice as many speculative-grade than investment-grade companies because the former are more vulnerable to a downgrade, as our default statistics illustrate. | |||

[[File:Fig4_rating_actions_by_type.jpg|700px|center]] | |||

In half of the cases in our sample, a natural catastrophe was the main trigger for the rating action. In the remainder, it was a contributing factor: often, other more material negative developments had already weakened the credit profiles of companies affected by a catastrophe. As a consequence, the natural catastrophe led to downgrades in the vast majority of those cases. By contrast, in 50% of cases when the natural catastrophe was the main trigger, the negative rating action was a revision of the outlook to negative, which was resolved with a rating affirmation. | |||

In about 40% of cases, natural catastrophes directly affected the operations of the company by physically disrupting its operations. For one third of cases, the main negative effects were indirect and focused mainly on the company’s supply chain. In the remaining cases, the widespread market and economic disruptions caused by natural catastrophes adversely affected the company’s credit profile. This caused unfavorable price movements and increased price volatility. In certain cases, the market and economic disruptions led to simultaneous negative rating actions on several companies operating within the affected sectors, two examples being power companies and automakers in Japan. | |||

==Katrina and Tōhoku took their toll== | |||

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in 2011 constitute the two biggest natural catastrophes of the past 10 years. They are also responsible for triggering almost 50% of rating actions in which natural catastrophes were a factor. Katrina, in particular, was behind almost all of the cases that ended in default. The effects of Katrina were wide-ranging, from large direct losses to major supply chain disruptions and price increases across a wide variety of industries. | |||

The most notable company that the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami affected was the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), the owner of the Fukushima nuclear power plant that was severely damaged by flooding caused by the tsunami. The Japanese government’s subsequent request to shut down nuclear reactors for safety inspections following the Fukushima disaster exacerbated the tsunami’s effect on TEPCO’s business. As a result, we downgraded our long-term corporate credit rating on TEPCO to ‘B+’ from ‘AA-’ between March and May 2011. Other power companies with nuclear operations that we rated in Japan similarly suffered multi-notch downgrades. The earthquake also caused widespread market disruption, which led us to revise our outlook on several Japanese automakers. | |||

Natural catastrophes don’t cause disruptions for all companies. Those whose business focuses on providing assistance during natural catastrophes could benefit, for example. By contrast, fewer-than-expected natural catastrophes could adversely affect such firms. In such instances, this has contributed toward negative rating actions. Other companies can benefit from higher prices as a result of natural catastrophes or because of reduced market competition if their peers suffer losses. However, these positive effects are rare. | |||

==Climate change and global trade links raise the stakes== | |||

Looking ahead, however, the picture is less certain. Growth in exposure in areas with high risk to extreme events, coupled with increased integration of the world economy through complex global supply chains, may exacerbate the impact of natural catastrophes. At the same time, the effects of climate change may increase their severity and frequencies. Scientific evidence, as summarised in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [http://ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/syr/AR5_SYR_FINAL_SPM.pdf ''Climate Change 2014''] report, points in that direction. In essence, higher temperatures will lead to more heat waves and droughts. Because warmer air can hold more moisture, the likelihood of extreme rainfall and subsequently floods will increase. Furthermore, rising sea levels caused by global warming are likely to increase the impact of coastal flooding during storms and high tides. | |||

If such extreme events were to occur, companies’ catastrophe insurance and overall disaster risk management could, in our view, become considerably less effective. The Japanese earthquake of 2011 provided a glimpse of what could happen when the magnitude of the event exceeded the levels assumed in the design of some of the tsunami protection measures, which as a consequence proved inadequate. | |||

In an increasingly interconnected world, a major local natural catastrophe affecting an important link in the global economy is likely to have a worldwide and long-lasting impact. Moreover, certain risks may become difficult and costly to insure as the likelihood and cost of natural catastrophes events increases. For instance, following large insurance losses from contingent business interruption (CBI) resulting from the Tohoku earthquake and the Thai floods in 2011, insurers tightened up insurance policy conditions; increased rates; and, in some cases, reduced the insurance coverage for some companies. (CBI is an important tool for companies to protect themselves against losses as a result of supply chain disruptions.) | |||

It’s unlikely that any company on its own can take adequate risk measures or purchase sufficient insurance to protect itself in the event of extreme natural catastrophes. Therefore, we consider that the international community as a whole will need to improve the resilience of the global economy to natural disasters so that their impact on companies is manageable. Climate change will in our opinion only add to this challenge. | |||

Because we expect the frequency of natural catastrophes, along with their economic effects, to increase in the future, companies will in our view need to improve their level of disclosure about their exposure to such events. This will allow investors and analysts to assess how material natural catastrophe is for the companies they invest in or analyse. In that regard, we consider that the [http://www.un.org/climatechange/summit/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2014/09/RESILIENCE-1-in-100-initiative.pdf 1-in-100 Initiative] should provide more insight into the resilience of companies to such events. The aim of this initiative is to promote companies’ disclosure of their exposure to natural catastrophes. It looks to participating companies to disclose the maximum probable annual financial loss that they could expect once in a hundred years (that is, with a 1% chance of occurring). | |||

==So far, so good; but the future could be very different== | |||

Generally, companies have managed to adequately withstand the effects of natural catastrophes over the past 10 years through a combination of liquidity management, insurance protection, disaster risk management and post-event recovery measures. In the future, however, the world could be hit by events that are significantly more devastating than recent ones. We believe such events could lead to a more widespread weakening of corporate credit profiles and subsequently to more downgrades than in the past. | |||

==Notes== | |||

Please refer to the [https://www.spratings.com/corporates/Understanding-Ratings-2.html Standard & Poor's website] for more information about ratings and read its disclaimers [http://www.standardandpoors.com/en_US/web/guest/regulatory/legal-disclaimers here]. | |||

''Under Standard & Poor’s policies, only a Rating Committee can determine a Credit Rating Action (including a Credit Rating change, affirmation or withdrawal, Rating Outlook change, or CreditWatch action). This commentary and its subject matter have not been the subject of Rating Committee action and should not be interpreted as a change to, or affirmation of, a Credit Rating or Rating Outlook. | |||

''Copyright © 2015 Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC, a part of McGraw Hill Financial. All rights reserved. STANDARD & POOR’S and S&P are registered trademarks of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC.'' | |||

'' | |||

[[Category: | [[Category:Context_of_treasury]] | ||

[[Category:Ethics_and_corporate_governance]] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:30, 22 February 2018

| Risk management | |

|---|---|

| |

| Authors | |

| Miroslav Petkov | Standard & Poor’s, London |

| Michael Wilkins | Standard & Poor’s, London |

Introduction

While recent history shows that natural catastrophes may have not been a major rating factor on corporate credit quality in the past, their effect in the future may increase considerably if, as scientific evidence suggests, we experience more frequent and more extreme climatic events. If such extreme events were to occur, companies’ existing insurance and overall disaster risk management measures could, in the opinion of Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services, become considerably less effective. Therefore, we see improvements in companies’ disclosures about their exposure to natural catastrophes becoming more relevant to our ratings analysis.

The economic cost of natural catastrophes has risen significantly over the past 10 years (see Figure 1 below). However, through a combination of existing preventive measures, most of the companies we rate have managed to mitigate the impact of such events on their corporate credit profiles. Nevertheless, with scientists predicting an increase in extreme climatic events, firms’ vulnerability to natural catastrophes is in our view likely to be sorely tested.

Overview

- Generally, companies have so far managed to mitigate the effects of natural catastrophes through liquidity management, insurance protection, natural disaster risk management, and post-event recovery measures.

- However, the more frequent and more extreme climatic events many scientists predict could adversely affect companies’ credit profiles in the future.

- Greater disclosure of firms’ exposure to extreme natural catastrophes should, in our opinion, encourage them to bolster their resilience to these events and thereby aid transparency.

Catastrophes seldom trigger rating actions – yet

Although natural catastrophes can result in companies experiencing property losses and production and market disruptions, such events are not frequently a factor behind our negative rating actions. Since 2005, we have identified natural catastrophes (tropical storms, floods, droughts, and earthquakes) as the main or material contributing factor for at least 60 negative rating actions (comprising downgrades and outlook revisions). This compares with around 6,300 corporate credit downgrades on companies in total over that period. In addition, we revised our outlook on less than five companies to stable from positive as a result of natural catastrophes. Overall, we find that companies’ liquidity management, insurance protection, natural disaster risk management, and post-event recovery measures were adequate in mitigating the impact of natural catastrophes on their rating profiles during the period.

Energy and consumer products sectors most at risk

While our sample of negative rating actions is too small to draw robust statistical conclusions, our analysis provides insights into how and when natural catastrophes can affect companies’ creditworthiness. No sector is immune to the effects of natural catastrophes. However, the energy sector (through a direct impact on production and distribution facilities and market dislocation) and the consumer products sector (through supply chain and market disruptions) appear most exposed, together representing more than one half of the affected sample. This is about double the proportion of rated companies that make up each of those sectors.

In around 40% of cases, natural catastrophes led to a one-notch downgrade. In a further 30%, we assigned a negative outlook that we subsequently resolved by affirming the rating. However, on average it took about 15 months for the credit profile of these latter companies to recover sufficiently for us to revise the outlook to ‘stable’. Across the rest of the sample, natural catastrophes contributed to multi-notch downgrades, and in about 10% of cases to default. Overall, this affected nearly twice as many speculative-grade than investment-grade companies because the former are more vulnerable to a downgrade, as our default statistics illustrate.

In half of the cases in our sample, a natural catastrophe was the main trigger for the rating action. In the remainder, it was a contributing factor: often, other more material negative developments had already weakened the credit profiles of companies affected by a catastrophe. As a consequence, the natural catastrophe led to downgrades in the vast majority of those cases. By contrast, in 50% of cases when the natural catastrophe was the main trigger, the negative rating action was a revision of the outlook to negative, which was resolved with a rating affirmation.

In about 40% of cases, natural catastrophes directly affected the operations of the company by physically disrupting its operations. For one third of cases, the main negative effects were indirect and focused mainly on the company’s supply chain. In the remaining cases, the widespread market and economic disruptions caused by natural catastrophes adversely affected the company’s credit profile. This caused unfavorable price movements and increased price volatility. In certain cases, the market and economic disruptions led to simultaneous negative rating actions on several companies operating within the affected sectors, two examples being power companies and automakers in Japan.

Katrina and Tōhoku took their toll

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in 2011 constitute the two biggest natural catastrophes of the past 10 years. They are also responsible for triggering almost 50% of rating actions in which natural catastrophes were a factor. Katrina, in particular, was behind almost all of the cases that ended in default. The effects of Katrina were wide-ranging, from large direct losses to major supply chain disruptions and price increases across a wide variety of industries.

The most notable company that the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami affected was the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), the owner of the Fukushima nuclear power plant that was severely damaged by flooding caused by the tsunami. The Japanese government’s subsequent request to shut down nuclear reactors for safety inspections following the Fukushima disaster exacerbated the tsunami’s effect on TEPCO’s business. As a result, we downgraded our long-term corporate credit rating on TEPCO to ‘B+’ from ‘AA-’ between March and May 2011. Other power companies with nuclear operations that we rated in Japan similarly suffered multi-notch downgrades. The earthquake also caused widespread market disruption, which led us to revise our outlook on several Japanese automakers.

Natural catastrophes don’t cause disruptions for all companies. Those whose business focuses on providing assistance during natural catastrophes could benefit, for example. By contrast, fewer-than-expected natural catastrophes could adversely affect such firms. In such instances, this has contributed toward negative rating actions. Other companies can benefit from higher prices as a result of natural catastrophes or because of reduced market competition if their peers suffer losses. However, these positive effects are rare.

Climate change and global trade links raise the stakes

Looking ahead, however, the picture is less certain. Growth in exposure in areas with high risk to extreme events, coupled with increased integration of the world economy through complex global supply chains, may exacerbate the impact of natural catastrophes. At the same time, the effects of climate change may increase their severity and frequencies. Scientific evidence, as summarised in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Climate Change 2014 report, points in that direction. In essence, higher temperatures will lead to more heat waves and droughts. Because warmer air can hold more moisture, the likelihood of extreme rainfall and subsequently floods will increase. Furthermore, rising sea levels caused by global warming are likely to increase the impact of coastal flooding during storms and high tides.

If such extreme events were to occur, companies’ catastrophe insurance and overall disaster risk management could, in our view, become considerably less effective. The Japanese earthquake of 2011 provided a glimpse of what could happen when the magnitude of the event exceeded the levels assumed in the design of some of the tsunami protection measures, which as a consequence proved inadequate.

In an increasingly interconnected world, a major local natural catastrophe affecting an important link in the global economy is likely to have a worldwide and long-lasting impact. Moreover, certain risks may become difficult and costly to insure as the likelihood and cost of natural catastrophes events increases. For instance, following large insurance losses from contingent business interruption (CBI) resulting from the Tohoku earthquake and the Thai floods in 2011, insurers tightened up insurance policy conditions; increased rates; and, in some cases, reduced the insurance coverage for some companies. (CBI is an important tool for companies to protect themselves against losses as a result of supply chain disruptions.)

It’s unlikely that any company on its own can take adequate risk measures or purchase sufficient insurance to protect itself in the event of extreme natural catastrophes. Therefore, we consider that the international community as a whole will need to improve the resilience of the global economy to natural disasters so that their impact on companies is manageable. Climate change will in our opinion only add to this challenge.

Because we expect the frequency of natural catastrophes, along with their economic effects, to increase in the future, companies will in our view need to improve their level of disclosure about their exposure to such events. This will allow investors and analysts to assess how material natural catastrophe is for the companies they invest in or analyse. In that regard, we consider that the 1-in-100 Initiative should provide more insight into the resilience of companies to such events. The aim of this initiative is to promote companies’ disclosure of their exposure to natural catastrophes. It looks to participating companies to disclose the maximum probable annual financial loss that they could expect once in a hundred years (that is, with a 1% chance of occurring).

So far, so good; but the future could be very different

Generally, companies have managed to adequately withstand the effects of natural catastrophes over the past 10 years through a combination of liquidity management, insurance protection, disaster risk management and post-event recovery measures. In the future, however, the world could be hit by events that are significantly more devastating than recent ones. We believe such events could lead to a more widespread weakening of corporate credit profiles and subsequently to more downgrades than in the past.

Notes

Please refer to the Standard & Poor's website for more information about ratings and read its disclaimers here.

Under Standard & Poor’s policies, only a Rating Committee can determine a Credit Rating Action (including a Credit Rating change, affirmation or withdrawal, Rating Outlook change, or CreditWatch action). This commentary and its subject matter have not been the subject of Rating Committee action and should not be interpreted as a change to, or affirmation of, a Credit Rating or Rating Outlook.

Copyright © 2015 Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC, a part of McGraw Hill Financial. All rights reserved. STANDARD & POOR’S and S&P are registered trademarks of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC.