Guide to risk management: Difference between revisions

imported>Doug Williamson (→1 Risks of trading: Correct alignment of currency rates) |

imported>Doug Williamson (Update for LIBOR transition.) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 236: | Line 236: | ||

* Changing market values of any debt outstanding. | * Changing market values of any debt outstanding. | ||

'''''Changing cost of interest expense or income:''''' This risk arises whenever a company refinances its borrowings, e.g. by issuance of commercial paper, drawdowns within a committed bank facility or making a bond issue. Therefore timing can be critical. Companies with debt charged at variable rates | '''''Changing cost of interest expense or income:''''' This risk arises whenever a company refinances its borrowings, e.g. by issuance of commercial paper, drawdowns within a committed bank facility or making a bond issue. Therefore timing can be critical. Companies with debt charged at variable rates will be exposed to increases in interest rates, while those companies whose borrowings costs are totally or partly fixed will be exposed to a fall in interest rates. The reverse is obviously true for companies with cash to invest. | ||

| Line 434: | Line 434: | ||

[[Category:Book_Export]] | [[Category:Book_Export]] | ||

[[Category:Financial_risk_management]] | |||

Latest revision as of 21:07, 25 April 2022

| Risk management | |

|---|---|

| |

| Author | |

| David Blackwood | Chief Financial Officer, Synthomer plc |

Introduction

An investigation into financial risk in a firm cannot be made in isolation and increasingly treasury must come out of its silo and manage financial risks in the context of the firm. Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) facilitates this by taking an integrated approach to risk management. However, although ERM is a fashionable concept, it can be difficult to conceive and even more difficult to implement.

Consider the following examples:

- Two divisions of a large multinational firm have traditionally been managed independently. Both have credit policies that are not considered centrally. It turns out that both share a large customer and management decides that the combined credit risk is too large for the firm.

- A firm operating in the transport sector is exposed to the commodity risk in fuel prices. While a response to this risk could be to consider it to be purely financial, an ERM view is to consider how selling prices might be adjusted to cope with the volatility in fuel prices, dealing with it as a financial risk over any short-term period. ERM takes into account both the commercial and financial dimensions, including competitive factors.

Enterprise Risk Management

ERM establishes co-ordinated risk management objectives with clear links to both the firm’s business strategy and to investor expectations. Using an ERM approach, all managers in the firm become risk managers and indeed risk management could be viewed as simply ‘management’. The treasurer’s speciality is managing financial risk, but crucially as part of the management team. A firm’s attitude to risk will be influenced, amongst other things, by:

- the philosophy of the firm: Many firms are naturally more cautious, conservative and prudent than others, and will try to manage risks down to a lower level of exposure;

- the financial structure of the firm: A firm with high financial gearing (high borrowings) is more at risk to market rates (interest rates in particular, but other rates as well) and is more likely to take steps to reduce this and other risks than a more conservatively financed firm;

- the volatility of its cash flows: A firm with high operational gearing or operating in risky markets is more likely to take steps to reduce other risks or, put another way, a firm with stable cash flows can accommodate increased financial risk. This is largely based on the sector in which the firm operates;

- the expectations of the financial community, notably:

- – shareholders; and

- – lenders, including bankers, bondholders and pension trustees;

- the advice given by specialists in various areas;

- the stage of its corporate strategy: For instance, firms emerging from radical change such as an acquisition or a major capital expenditure programme will be reluctant to accept any additional risks for some time;

- the stage of product development, if one product dominates the firm. Thus, for example, an infrastructure or construction project has high risk during the construction phase as compared to the operating phase, similar to the introduction of any new product;

- the size of its risks in relation to some benchmark: e.g. the current year’s earnings or the three-year strategic plan; and

- natural hedges within its business;

- the behaviour of its peer group, as firms will compete not only at the product level but also at the investor level, vying for capital. It is unlikely that one member of a peer group will go too far out of line with all the others.

A very useful way to view Enterprise Risk Management is to recognise four stages in reaching an approach to risk. Firstly, risk tolerance represents the amount of risk that the firm can actually bear. This could be represented by its capital, or by an amount of capital above a base amount of capital that cannot be put at risk. Secondly, risk appetite is the amount of risk that is actually desired. This might be seen in relation to the return sought by investors. Remember that reward is really only gained by taking risks, so limiting risk will limit reward. Thirdly, risk appetite leads naturally to risk budgeting, which is a way of setting out where risks in a firm should be taken. In treasury terms, we might see that if much risk is taken in the business model, then we need a very conservative approach in treasury. Finally this is documented in risk policy. This approach does require risk measurement and we address this challenge briefly in this article.

Risk classification

The classic way to proceed with ERM is to list all the risks that affect a firm and map them onto a grid where the two dimensions are a probability of the risk and the severity of the consequences if the risk event materialises. To enable the listing of risks a convenient classification is as follows:

- Business risks: The risks that arise from being in a particular industry and geography and from the chosen business strategy. Risks include wrong strategy, bad or failed acquisitions, new product failures, poor capital investment decisions, poor product mix, price and market share pressures, loss of key contracts, poor brand management, geographical and political risks;

- Financial risks: The risks include liquidity (including the inability to obtain further capital), counterparty credit (e.g. from depositing cash) and pensions and the market-based risks of foreign exchange, commodity and interest rates, as well as some risks that may also be considered operational such as fraud, errors in administration, IT risk;

- Operational risks: The risks that arise in the operational procedures that the firm uses to implement its strategy. Risks include skills shortage, lack of raw materials, physical disasters, and quality problems; and

- Compliance risks: The risks that derive from the necessity to ensure compliance with laws and regulations which, if infringed, can damage a firm. Risks include breach of listing rules, breach of regulatory requirements (in a non financial firm these include pension regulations and those surrounding utilities), breach of domestic Companies Act requirements, tax issues, health and safety breaches and environmental problems.

There are alternative classifications, such as geographical analysis or an approach from Strategic, Tactical and Operational directions, although there are also others.

It can useful at this stage to consider leading indicators to risk, so that each risk identified as part of the classification might be ‘sparked’ by events or measures. So an automotive manufacturer might notice that its competitors have introduced new models or plan to do so in the next two years. A supplier to the oil industry may suffer if the oil price falls. These could be leading indicators of competitive risk and could be Key Risk Indicators (KRI).

Risk response

For each risk there are broadly four possible alternative responses by the firm:

- Avoid the risk.

- Accept the risk and:

- – retain the risk; or

- – reduce (perhaps to zero) the risk by internal means; or

- – transfer the risk externally.

In deciding how to manage each risk it is useful here to remember that investors’ motivation for the ownership of a firm is to seek extra reward from the extra risk compared to putting their money into alternative investments. The firm’s response to risk is influenced by this and specifically investors generally expect the firm to take (accept) business risks but equally expect the firm to take action to lessen (by transfer, management or avoidance) most other risks. This principle generally holds true – but there are several instances where an investor might seek other (financial) risks alongside the underlying business risks. This would be the case where the underlying business model does not provide sufficient returns for equity investors but the added financial risk in the form of leverage achieves the desired returns. This would happen in a Private Equity investment, for example, where investors gear average business returns to higher and riskier returns. As another example, utilities and property companies typically have high leverage to achieve adequate equity returns. An ERM philosophy is important, as it enables the firm’s entire risk management – including business, financial and operational risks – to be aligned according to investor expectations. For example, investors will wish to take the risk of the launch of a new product but will not wish to see the firm sink money into pension schemes because of failed investments or pay fines because of polluting accidents.

This leads us to understand why risk should be managed. If the value of a firm is the future cash flows discounted at the return required by investors, and their required returns are linked to risk, then of two firms with the same expected cash flow, the firm with the lower risk will be worth more. Avoidance of financial distress is another key aim of risk management, and is arguably the most important aim.

We now need a framework to see how to manage this process.

Risk management framework

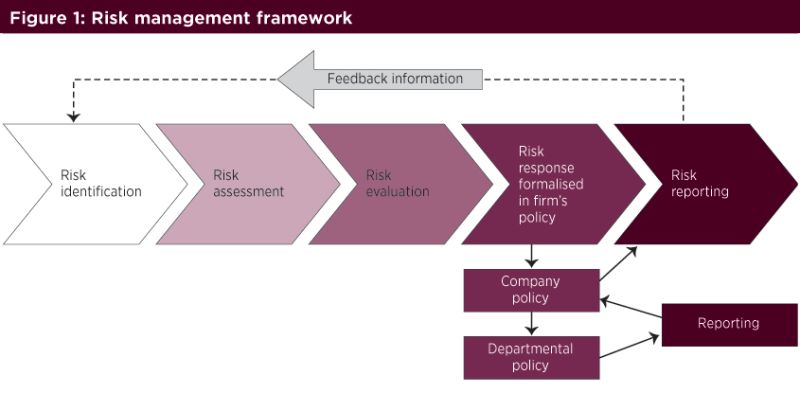

This framework, shown in Figure 1, has the following stages:

- identify risks to the organisation’s strategy;

- make an initial qualitative assessment of the risks, estimating the probability and impact of each;

- make a detailed quantitative evaluation of the risks, to better define their probability and impact and to establish a measure of the risk;

- set out the responses to each risk, taking account of linkages between different risks, formalised in company and departmental (including treasury) policies;

- report on the outcome of policy execution, i.e. the progress of risk management, specifically to see if the response chosen has reduced the risk; and

- periodically feed back and re-evaluate the whole risk management process.

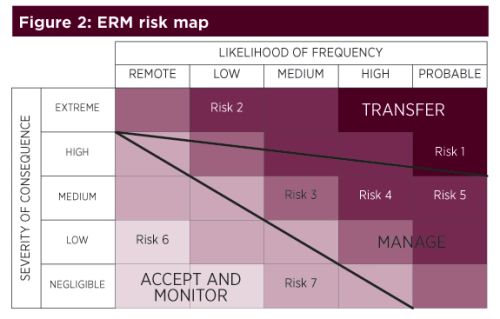

With this framework we can now see how we might construct an ERM approach and map risks onto a grid that looks similar to Figure 2.

On this risk map, a firm has identified five categories of both likelihood and severity of risk. It has further mapped seven particular risks on this grid, thus forcing action. Risk 1, for example, has a high priority for action. If a particular risk is not a business risk, i.e. the activity giving rise to the risk is not core to the business strategy, it might be appropriate to avoid the risk. Risks that are not avoided have to be accepted and either retained, or reduced internally or transferred. Typically firms will reduce risks by internal means before transferring any residual risk externally, to save on the costs of transferring the risk.

Each risk requires objectives and a policy so that each layer of management knows what it is trying to achieve, what power it has to do this and how success in management of the risk will be measured. Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are useful tools here, driving regular reporting. A KPI could be considered a measure of the risk, or the effect on the company, in contrast to the KRI. A policy for each risk must cascade down the firm to reach individual departments so each knows their own role in the management of the response to each risk.

By identifying risks individually in this process, there is a danger that each risk is then treated on its own, in fact the very opposite of what ERM is trying to achieve. Each risk should therefore be seen in the context of the firm as it is taken through the framework. An important point here is to recognise how some risks might interact to increase their combined risk and how some might interact to reduce the combined risk. If an automotive manufacturer with two major brands were to launch a replacement model from each brand in one market segment simultaneously, that could well increase risk. Conversely a capital equipment manufacturer making bids for many different projects has increased his chance of gaining contracts, thus reducing risk. Diversification of risks is a key part of modern risk theory for which ERM is ideally suited to manage. Diversification works when correlation between risks is negative or low and so understanding correlations is important for the risk manager.

Financial risk

We now turn to the financial risks in which a treasurer is most usually considered the “custodian” but, as we have seen in an ERM context, not exclusively. In seeking to define financial risks, this is sometimes done by trying to identify where losses or financial distress might be caused by adverse events or market movements. However, it can be more complicated than that. Financial market risks in particular can move in favour of the firm and a response to risk may be to seek to take advantage of such favourable movements, rather than simply to reduce or transfer the risk. Sometimes the reduction or transfer of risk might be a mistake. If, prior to a recession in which its profitability falls, a firm fixes interest rates to achieve what seems to be a certain and therefore less risky interest charge, it will not be in a position to take advantage of falling interest rates, thus increasing its risk of insolvency. In that case an apparent policy of risk avoidance has increased risk, and quite possibly weakened the business’s competitive position compared to competitors who have floating rates. This example reinforces the need to consider risks and their mitigation very carefully.

Liquidity risk

Liquidity risk, perhaps the fundamental risk of treasury, is the risk that a firm ceases to have access to the cash it needs in order to meet its financial obligations as they become due. It has several dimensions. First it applies at the overall level of the firm in its most consolidated form, let us call it “funding” liquidity risk, and it will arise where, as is common with corporate groups, financing is managed at parental level. Second is the risk of breakdown in markets which usually operate smoothly, let us call it “market” liquidity risk. Finally is the recognition that, in international groups, liquidity must be available in all jurisdictions where the firm operates. The firm must fund its operations wherever they are in the world (although strictly it could decline to fund an un-guaranteed legal entity). Because survival of the firm is at stake, this is arguably the biggest risk facing the firm. If a firm fails, equity investors (usually) lose everything. If a firm survives (even marginally), there is a chance for equity investors to make good returns.

- Funding liquidity risk: This is the risk that the firm fails to obtain funds to meet cashflow obligations and may arise from breaches of covenants within its loan agreements, financial or otherwise. These are mostly caused by failing financial performance, but not always. Other causes include an inappropriate financing strategy, perhaps due to failure to diversify its funding sources or having too high a proportion of its debt maturing at one point in time. Even if none of these actually happens, a poor business model may lead to an inability to finance or refinance.

- Market liquidity risk: This is the risk that financing will be disrupted by closed or illiquid markets. It can range from the drying up of commercial paper or bond markets to the inability to do simple foreign exchange swap transactions.

Liquidity risk is probably the most significant risk that the majority of treasurers have to manage. It is a risk which, if it materialises, may result in the company being unable to pursue its chosen strategy, especially if this requires expansion through acquisition or organic growth, or if it assumes the successful re-financing of existing debt.

Lender relationship risk

Considered by many to be a part of liquidity risk, the fostering of lender relationships is key to being able to raise borrowing at any time. Banks are often the first port of call but lending by institutions forms an essential part of the lending for many firms in both public and private markets. Since the financial crisis the place of banks in the list of lenders has undergone substantial change. In some sectors, particularly for very high grade borrowers, banks do not feature highly as a source of funds, but in the smaller firm sector, there is no real alternative, although banks are in fact reluctant to lend heavily in that sector. Banks themselves are under enormous pressures from revised regulations (notably Basel III but many regimes have additional approaches, such as Vickers in the UK and the Volcker rule in the US) following the crisis. Lenders retain an impression of a firm from previous dealings and so issues of routine communication, keeping promises, avoiding surprises, ancillary business, loan amendments and fair pricing are all factors which can be managed in order to keep the goodwill of lenders. Relationship banking is a technique used by many treasurers to approach this issue.

Credit rating risk

Only a few debt capital markets can be accessed without either a short or long-term public debt rating and even bank lenders (who do not require a firm to have a credit rating) take account of ratings. The cost of this debt finance and, equally important, the conditions of the finance, is closely related to the firm’s credit rating. Many firms target particular financial ratios to manage credit rating risk and communicate this to the rating agencies through good and easy relationships.

Foreign exchange/commodity risk

These risks can increase profitability as well as cause losses compared to expectations and the treasurer may well respond to risk by adjusting a risk profile to take this into account.

It is helpful to separate these risks into those risks arising from trading and those arising from ownership. A business (or indeed any of its competitors) that has more than one currency or commodity element in any of its sales or costs will have risks arising from trading. A business that owns operations with different reporting currencies will have risks of ownership. Let us look at some examples to understand this better.

A domestic airline will collect its fares in its local currency, as its market is purely domestic, but will pay many of its costs in US dollars, such as fuel and indeed the aircraft cost. This risk arises in its trading.

A Singapore-based consultant owns a US-based subsidiary, the business of which is completely domestic and has no exposure to any currency other than the US dollar. The Singapore parent must translate the US dollar revenues and balance sheet when it reports in Singapore dollars. There is no need to physically sell any of the US dollars. This is of no consequence to the US subsidiary, which think only in US dollars, and so is a risk of ownership.

Commodity risks can only be risks of trading.

1 Risks of trading

The types of risk considered here are transaction risk, pre-transaction risk and economic risk.

- Transaction risk: Transaction risk arises on the items that have been committed to by the firm which will require an exchange of currency or commodity at some stage in the future. They are usually short term and on the balance sheet although large capital projects such as infrastructure projects may extend over several years. The point is that the exposure is certain. Typical examples include purchase of stock in a foreign currency, but can also include dividends and royalties and so on. Inter-company dividends might give rise to transaction risk but these might need to be considered as part of translation risk (see below) arising from ownership of the dividend stream.

Transaction risk requires a treasurer to get out and see what’s going on in his firm, a classic case of ERM in action. He or she will not know by sitting at their desk, and even getting reports from operational management may not be as reliable as he/she thinks.

- Pre-transaction risk: These are contingent risks and arise where the firm has made an offer to enter into a commitment that would become a transaction risk if the offer is accepted. Examples include publishing a price list in the firm’s own currency which has foreign currency or commodity costs inherent in it, publishing price lists in a foreign currency under similar circumstances and any case of bidding for a contract with costs which are not certain. Risk increases with the length of time that the price list is valid or the price is left open.

- Economic risk: This is perhaps best described as the risk arising on future transaction streams. It is essentially about the competitive position of the firm. Market rates may move so that the pricing model of the firm becomes less competitive. The risk reflects the fact that no hedge lasts forever and the firm’s marginal exposure to market rates cannot be avoided.

As an example consider a German engineering firm exporting to the US, with its major competitor in the US being a Japanese manufacturer. Such a company has exposure not only to the €/$ exchange rate on its transactional and pre-transactional exposures, but also has exposure to €/JPY. If, in the future, the yen weakens against the US dollar more than the Euro weakens (reflected in the €/JPY rate), then the Japanese competitor will be in a stronger position, able to either reduce its price to reflect this, or maintain pricing and make higher margins.

This is an example of ERM in practice as the response to changing exchange rates in both firms is likely to be as much about managing the commercial relationship with customers over a long period, as about immediate action in the financial markets.

| Example of the impact of exchange rates | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Consider a UK company which has an investment in the US. On the consolidation of this investment, the sterling value of these dollar assets will vary depending on £/$ exchange rates ruling at the date of consolidation, and the domestic value of the related foreign currency earnings of the investment will vary depending on the average exchange rate during the year. | |||

| $ | £ | £ | |

| million | million | million | |

| 1.50 | 1.60 | ||

| Gross assets | 1,000 | 667 | 556 |

| Liabilities | 250 | 167 | 156 |

| Net assets | 750 | 500 | 469 |

| 1.55 | 1.65 | ||

| Net profit after tax | 150 | 97 | 91 |

2 Risks of ownership

- Translation risk – accounting: Firms with subsidiaries with a functional currency different from the reporting currency of the parent (usually but not always in a foreign country) will find that the translation of “foreign” balance sheets and income statements will vary between reporting periods. Translation of the balance sheets amounts to calculating the accounting net worth of these subsidiaries and seeing how it has changed due to foreign exchange movements. Any foreign currency debt also falls into this basket. Translation of the earnings will similarly vary from period to period.

Treasurers have different views as to whether these constitute real risk. They arise merely because of the need to draw up financial statements and they are a manifestation of the overall business risk. Owners of the firm carry the risk and reward of trading overseas and so must expect such translation differences.

Nevertheless, some treasurers respond to this risk with very precise programmes to hedge earnings into “home” functional currency from year to year. Foreign investments are also often financed by debt in the currency of the investment to reduce the size of the net investment and care taken with how to manage the interest and dividend flows.

Where translation risk certainly may cause problems in some firms is where financial ratios (such as interest cover, gearing and other ratios measuring credit risk) may change because of currency fluctuations, causing problems with financial covenants. Additionally it can give rise to a real risk of ability to repay debt or generate dividends.

For example, a firm with cash generation in one currency and debt or pension or dividend obligations in another faces real risk in its ability to service them.

- Translation risk – economic: An alternative way of looking at translation risk is to consider the economic value of overseas businesses. The economic balance sheet of a company captures the idea that its businesses are assets, and its market capitalisation reflects the fair value of these businesses (translated at prevailing exchange rates) adjusted for other non-business assets and liabilities (debt, pension deficits other liabilities etc). This is effectively the way an equity analyst looks at a company. A company with a sterling listing with a significant US business is exposed here. A significant rapid strengthening of sterling against the dollar, absent any other effects (see economic risk below) would cause a rapid loss of value to sterling shareholders. This would be readily visible if the overseas business were to be sold after such a movement in rates, and would become visible over time as the reported earnings deteriorate on weaker accounting translation of results. This is a major risk area for the treasurer of an international group, and is usually dealt with by holding a proportion of overall debt in the related overseas currencies.

Interest rate risk

Interest rate risk is the exposure of the firm to changing interest rates. It has three main dimensions:

- Changing cost of interest expense or income.

- Changing business environment as a result of changing interest rates leading to changing business performance.

- Changing market values of any debt outstanding.

Changing cost of interest expense or income: This risk arises whenever a company refinances its borrowings, e.g. by issuance of commercial paper, drawdowns within a committed bank facility or making a bond issue. Therefore timing can be critical. Companies with debt charged at variable rates will be exposed to increases in interest rates, while those companies whose borrowings costs are totally or partly fixed will be exposed to a fall in interest rates. The reverse is obviously true for companies with cash to invest.

One interesting dimension of this risk is on future investments, rather than on just re-financings. Imagine an airline which needs to continually invest in new aircraft. These aircraft tend to be financed individually and so each new aircraft will come with an interest rate fixed in the market at some time, and therefore subject to risk. So a new aircraft financed at a higher interest rate will need to earn more to repay itself. Seat prices would need to rise, all else being equal.

Another aspect of interest rate risk is the risk of changes in margin or spread, usually following a refinancing. Lending margins (spreads) over benchmark bonds rose significantly during the credit crisis and while they have largely returned to pre crisis levels (for investment grade and larger firms at least), firms refinancing bank facilities or capital market debt face this risk, and commercial paper issuers and other users of uncommitted facilities will face this every day.

As a response to both these elements of interest rate risk, the choice of borrowing instrument used can be made to allow a firm to fix or float either element of its overall interest rate. A fixed rate bond issue fixes both the underlying interest rate and the spread for the life of the bond. A committed revolving bank facility fixes the margin for the life of the facility (subject to pricing grids) while allowing the underlying interest rate to fluctuate. Commercial paper issuance means both the underlying interest rate and the spread will fluctuate. Interest rate swaps are also used as a classic response to alter the fixed/floating mix of the underlying interest rate.

Changing business environment: Changes in interest rates also affect businesses indirectly through their effect on the overall business environment. Generally, as interest rates and thus the cost of borrowing rise, usually as a response by the authorities to higher economic activity, economic activity falls and profitability is depressed as firms face lower sales volumes in contracting markets. Some companies may find that they have a form of natural hedge against interest rate exposure. Common examples can be found in the regulated sectors such as the electricity industry or housing associations which are allowed to increase their charges by the Retail Prices Index (RPI). Interest rates tend to be higher when inflation is higher creating a natural offset. Nevertheless, this link can be a complex one, with some leading or lagging or even an inverted link, and it is notoriously difficult to model.

Changing market values of any debt outstanding: Changes in interest rates will change the value of fixed rate debt and investments. Investors in these instruments are heavily affected but it can be a risk to issuers (i.e. reflecting most corporate activity in these markets) in some circumstances, and is a particular risk for firms with future healthcare or pensions commitments. As interest rates fall, the value of liabilities rises and vice versa. In this area of pension commitments quite complicated forces have been acting in the past few years. Underlying interest rates fell through the credit crisis (as measured by government bond rates), pushing up liabilities by that measure, although the accounting valuation of liabilities did not rise so strongly because of the rise in spreads on (mainly financial) AA bonds. This highlights how difficult it is to measure these liabilities.

Although a corporate borrower will commonly report its bonds in issue substantially at their face values in its financial statements, should it wish to redeem the bonds early (e.g. from the proceeds of a rights issue), it will have to do so at their current market value (or according to other market norms), which may be significantly different.

Counterparty risk

Counterparty risk, also known as credit risk, is the risk that a counterparty fails to perform its contractual obligations. It is important in treasury transactions, primarily in the placing of deposits with governments, money market funds, banks and so on and in foreign exchange, commodity and interest rate derivative transactions. It is also important in customer and supplier relationships. If the counterparty fails, financial loss to the company may result. Counterparty risk is clearly best managed on a company-wide ERM basis to cover all instances of exposure, in much the same way as banks treat their corporate customers. In particular, it is easy to conclude there is no major single debtor risk when looking at a company by component operating divisions, but aggregating across divisions may present a different picture.

Other financial risks

Pension risk

This risk is covered elsewhere in this Handbook and in this article but is almost entirely based in defined benefit schemes and their equivalents around the world. The risk arises mainly in the changing underlying market and economic variables affecting assets and liabilities in a scheme, which is separate from its sponsoring firm.

A further risk arises, however, because a deficit can give rights to the scheme and can impact the ability of the sponsoring firm to pursue its strategy. This is usually found in the case where a sponsoring firm wishes to increase its financial risk, through a leveraged buyout, for example, or by gearing up to make an acquisition.

Weather risk

This risk reflects how a business is affected by weather. Although the risk can be transferred into the financial (and insurance) markets, the main problem both for economic and accounting purposes is establishing an appropriate correlation between business performance and the weather at the defined reference points.

Operational risk in treasury

This risk arises as a by-product of financial risk management activity, which necessitates the existence of a treasury department or treasury type activities undertaken by any person. It can be categorised as arising broadly from external events/business discontinuity, error or fraud.

External events/business discontinuity

Strictly, external events refer to events entirely outside the business, such as flood or seismic events, while business discontinuity is nearer the business, such as communications breakdown or market interruption. The effect of each on treasury is much the same.

Error

Many different types of error can arise in the day to day operations of treasury, from making transactions the wrong way round (e.g. buying instead of selling), making them in the wrong amount, paying the wrong counterparty in a transaction, failing to fund expensive overdrafts and so on, to preparing reports on the basis of wrong information, leading to incorrect decisions.

Fraud

Fraud is clearly the risk of misappropriation of funds or, also quite common, the inappropriate taking of risk decisions, such as taking large positions.

Management of financial risks

Remembering the order of approach in dealing with risks:

- identify;

- assess;

- evaluate;

- respond to each risk with a policy;

- report; and

- feed back.

We now consider how the treasurer may deal practically with the financial risks we have seen.

Identification of financial risks

This is best approached on a “bottom up” ERM basis, and the treasurer should get out and about to operating divisions/units to find out what they perceive to be the risks to their objectives, although the treasurer should have a good understanding of what to expect. There will also be some risks, e.g. translation risk, which are “centralised” and can be viewed as “ownership” risks. Liquidity should be viewed from all directions.

This research is often the most difficult part of any risk strategy. Treasurers may not have the time to make full investigations of their business and reliance on reporting from them can be unreliable. For example, a full analysis needs to look at pricing policy, orders, any risks dealt with contractually, purchasing policy, competition and so on.

One common approach is to analyse the income statement and balance sheet on a line by line basis and identify those financial risks which apply to each line. This analysis might be conducted with the set of questions illustrated for each main subject. This approach might usefully be extended to the cash flow statement to check for any obvious liquidity or other issues such as changes in working capital, and investment or disposal programmes. Other approaches (more suitable for discussions with non-financial personnel) may be to identify key business drivers or business processes and analyse the financial risks inherent in those drivers or activities.

KRIs can be useful here and can act across more than one risk type. For example suppose that an international group is operating in one particular country, where elections are to be held in two years’ time and where there is intense speculation over the successor government and its policies. That could be a KRI for many types of risk.

| Illustration |

|---|

|

Income statement

Balance sheet

|

Assessment of financial risks

To map risks onto the ERM risk map requires them to be initially assessed for severity and probability and is essentially the first stage in ranking them for priority treatment. Risk assessment is a qualitative attempt at ranking risks by assigning them an initial probability and impact, and plotting them on a risk map such as that illustrated above. The process sets a priority order (from high probability/high impact to low probability/low impact) for the more detailed risk evaluation phase.

Evaluation of financial risks

Evaluation of financial risks takes the assessment to a further stage of analysis and, crucially, requires the creation of a measure of the risk.

This measure is important because it allows the creation of an objective for that particular risk. Thus in liquidity risk we may not simply say that a firm has sufficient cash for its needs but we should measure the headroom (cash and undrawn facilities available) over the next, say, 18 months.

With a measure, even if qualitative, we can design a Key Performance Indicator (KPI) for that risk and then target a particular level and see what effect certain actions have on that KPI and use it as a basis for reporting. Examples of measures that might be used in risk management could include:

- Probability of interest cover falling below threshold as a measure of interest rate risk.

- Headroom over the next two years

- Facilities maturing in the next two years

- Value at risk from transaction exposures.

- Number of non-bank lender meetings held every year and participation at meetings.

- Size of panel of banks to be derivative counterparties.

Some of the quantitative tools used at this stage include sensitivity analysis, scenario analysis and mathematical techniques. Qualitative measurement may often also be used. Whatever the process or technique selected for measuring or assessing financial risk, it should be appropriate in the context of a company’s overall governance, control and risk management process.

- Sensitivity analysis: This technique assesses the impact of a notional change in the market rate or price of the underlying risk. It is often made by comparing the magnitude of such notional changes against a benchmark such as the underlying budget or forecast for the revenue, cost or balance sheet item.

For example, Company A has $500m of borrowings all at floating rate. It measures the risk of borrowing at a floating rate by assessing the impact of a 1% increase in US dollar interest rates – $5m. This would be evaluated in the context of budgeted interest expense for the year of e.g. $27m and budgeted profit before tax of $100m. The same approach can be applied to foreign exchange, commodity, equity risks and other financial risks that are dominated by financial prices.

- Scenario analysis: This assesses the impact of a notional change in a number of market rates or prices which may affect multiple risks. This assessment can again be made by comparing the magnitude of such changes against a benchmark such as the underlying budget or forecast for the revenue, cost or balance sheet item. Scenarios can be run using computer models to change a variety of input variables in a simulation approach; or it can be run on a qualitative basis: “What effect might an extended recession/speedy recovery have on the price of oil?” “What are the implications of the oil price for the strength of the dollar?”

- Mathematical techniques: These include techniques such as Value at Risk (VAR) and Monte Carlo simulations, touching also on scenario analysis. VAR is a relatively simple technique to source a single number for the risk in a portfolio at a certain confidence level. It does rely on being able to use certain statistics for each asset class such as volatility and correlation between asset classes, which can be difficult to source and use with confidence. It does, however, use probability, which sensitivity analysis and scenario analysis do not easily accommodate. Monte Carlo techniques use multiple scenarios to find a distribution of possible outcomes in a particular case. Such techniques have been used in the analysis of defined benefit pension schemes for many years but have not been widely used in the corporate arena or in ERM. They are helpful – but they have some serious limitations and need to be used appropriately.

- Qualitative measurement: Not all financial risks are influenced by changes in market rates and prices. Examples of such risks are bank relationship risks and liquidity risk. A firm may assess the significance of these risks according to their potential impact on its strategic objectives if they were to arise. For example, the likelihood of being unable to raise long-term finance is likely to have significant implications for a company with an expansionary strategy involving substantial amounts of new finance.

Policy response

The response of the firm to a particular risk should be set down in a policy. One example of the policy construction could be as in the following example.

| Example: Policy construction | |

|---|---|

| Item | Remarks |

| Policy name | Give the policy a name |

| Policy objective | Identify the risks the policy is to address |

| Policy direction | Give the overall direction of approach to these risks |

| Risk measurement | How is this risk measured |

| Benchmarking | Establish externally available benchmarks if possible |

| Responsibility / oversight | At what level / who should have ultimate responsibility for the management of this risk? |

| Procedures | What controls or procedures can be put in place to control this risk? |

| Decision making | Provide an overall framework for decision making by managers and staff |

| Policy Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) | Select policy KPI(s) to be used to measure the risk and monitor performance. What target is selected for the KPI? |

| Reporting / feedback | How should performance against the policy KPI(s) selected above be reported/fed back? |

| Continuous improvement | What procedures are required to ensure that the policy is kept up to date, is adhered to, and has the desired effect? |

This policy relates directly to a risk, and tells us all we need to know about how to manage it, from measurement to who has authority to make decisions to what the target is for the measurement, i.e. the KPI. It concludes with how the KPI is to be reported and what can be done to improve the process or modify it as circumstances change. Examples of targets for KPIs leading on from the measures shown above could be:

- Interest cover to be greater than 3.0 on a 95% confidence basis over an 18 month period.

- Forecast headroom over the next two years to always exceed $5 million

- Facilities maturing in the next two years to be less than 15% of all facilities

- Value at risk from transaction exposures to be less than £100,000 on 95% confidence basis over the life of the exposures.

- Non-bank lender meetings to be held every six months with target of 30% participation of lenders in the register.

- Six banks always to be available as derivative counterparties.

Reporting and feedback

The process of reporting and feedback are simple in concept and should be based on the measure and KPI selected for the particular financial risk. Feedback is crucial to manage any weaknesses in either the whole risk management process or the particular risk being reported on and is vital to keep risk management aligned with overall enterprise developments. Without reporting and feedback the process will become sterile.

Conclusion

Financial risk, often seen as the preserve of the treasurer, needs to be seen in the context of the firm. Plenty of techniques are available for the management of financial risk but the treasurer needs to ensure that the processes used are always approved at the highest level of the firm, with easy to understand targets and applied rigorously, including reporting so that all layers of management are kept fully informed. The treasurer can then be seen to be fully contributing to the success of the firm in reducing risk.