The RMB as a global currency: progress and challenges ahead

| Risk management | |

|---|---|

| |

| Authors | |

| Li-Gang Liu |

Chief Economist Greater China |

| Nicholas Hill |

Director Global Diversified Industries, Europe International and Institutional Banking |

Introduction

China is now at the crossroads of a major economic and structural rebalancing, and its success will determine whether it can return to a sustainable path of economic growth. Central to the success of the rebalancing act is China’s financial and capital account liberalisation, with RMB’s internationalisation being a major initiative.

In the past 30 years China has progressed quickly and become the factory of the world. During the process, millions of Chinese have been lifted out of poverty.

The rapid industrialisation has also led to rapid urbanisation, making China the largest consumer of commodities, leading to an economic boom in resource rich economies as well. Since the new millennium, China has quietly become the world’s second largest economy.

While China’s trade has been fully integrated into the global trading system, its finance has not. Chinese yuan, also called renminbi (literally means people’s money), remains a local currency. Cross border fund flows are still subject to various degrees and forms of restriction. Capital controls, especially on outbound, and a rigid exchange rate regime have led to the rapid accumulation of foreign exchange reserves. To some extent, a large part of the capital inflow has become base money and inflated a property bubble in China. To prevent it from accumulating reserves further, China has also started to promote international uses of the RMB, alongside its ongoing exchange rate reform.

In December 2003, China began to allow Hong Kong banks to do some simple personal business in RMB. But it wasn’t until 2009 that cross-border trade settlement in RMB was introduced, accelerating the RMB internationalisation process. Since then, the offshore RMB market has blossomed with new policies being rolled out and market institutions built. Meanwhile, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) increased its signing of bilateral cross currency agreements with other central banks. The Ministry of Finance (MoF) has issued RMB-denominated bonds in the Hong Kong market in an attempt to establish a yield curve for the CNH bonds offshore.

With RMB internationalisation in its sixth year and progress accelerating, it is a good time for us to appraise what has been achieved to date and ascertain the direction of future developments. The big question is what the RMB’s future holds? Will the RMB become another global or a reserve currency alongside AUD, NZD, EUR, JPY or even USD?

This article highlights the latest development in the offshore RMB markets. We argue that economies that have strong trade and investment ties with China, such as Australia, appear to have significant potential to become offshore RMB centres and benefit from the next wave of China’s capital account liberalisation. However, the policy initiative is not free from challenges, which should not be overshadowed by market excitement.

| Things to watch |

|---|

|

The direct conversion between AUD and CNY paves ways for a more active use of the RMB in Sino-Australia trade and investment flows.

|

Hong Kong’s market is still evolving

As a Special Administrative Region of China with a sophisticated financial market, Hong Kong has often been used as a pilot to test China’s economic reform policies. The RMB internationalisation is no exception. Indeed, China’s 12th Five-Year National Development Plan (12th FYP) explicitly states that Hong Kong will be supported to develop the offshore RMB business.

With a large volume of cross border trade with Mainland China, Hong Kong has benefited from the establishment of RMB settlement and clearing facilities, and has built up a large pool of RMB deposits. Now, financial institutions in Hong Kong can offer a full range of RMB products and services:

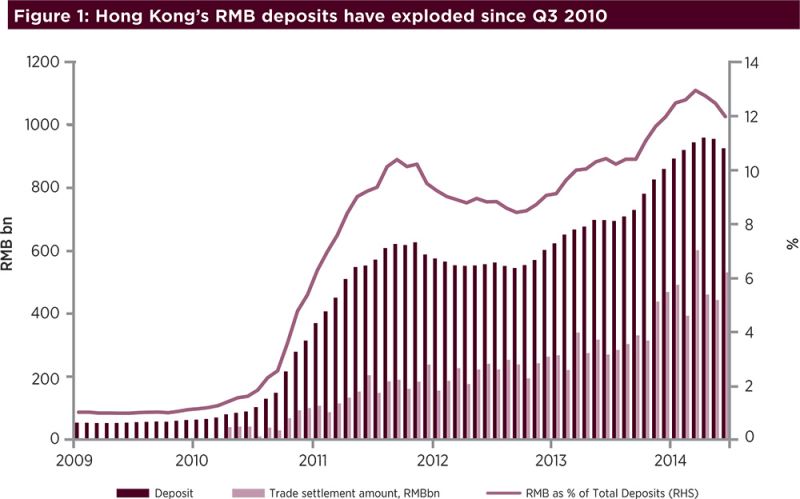

- Deposits: Total RMB deposits reached RMB956bn, representing 12.5% of deposits of the entire banking sector as of May 2014 (Figure 1). Both local residents and non-local residents are allowed to open an RMB deposit account. While local residents can buy and sell RMB using the onshore exchange rate (CNY), they are subject to a daily conversion limit of RMB20,000. However non-residents are not limited by this rule as their transactions are based on the offshore exchange rate (CNH).

- RMB lending: RMB bank lending has expanded significantly over the past few years, with outstanding RMB loans amounting to RMB116bn at end-2013, a 47% increase from end-2012. However, the absolute size of RMB lending remains very small.

- Trade settlements: In 2013, the total remittance of the RMB for cross border trade settlement achieved 30% growth and exceeded RMB3.8trn (USD620bn), representing 83% of total external trade of Mainland China settled in RMB.

- Interbank payments and transactions: The Hong Kong RMB real-time gross settlement (RTGS) system handles a growing volume of cross-border and offshore transactions, with average daily turnover of RMB700bn in March 2014, doubling year on year.

- Products: Spot and forward remain the most popular transactions, while CNH option and cross-currency swap (CCS) markets are also increasingly active. A total of 15 banks that are active in the offshore RMB market have contributed USD/CNH quotes for the calculation of the daily fixing published by the Treasury Market Association (TMA) since June 2011. In June 2013, the TMA launched a CNH HIBOR fixing with tenors from overnight to 12 months, calculated from the rates contributed by a panel of 16 banks that are active in the RMB interbank market. This development has provided a benchmark rate for product pricing in the offshore market.

- Securities market: Offshore RMB bonds, also known as dim sum bonds, have outperformed other asset classes in the securities market. The size of the RMB dim sum bond market rose by 31% to RMB310bn in 2013 (Figure 2). China’s Ministry of Finance issues sovereign bonds in Hong Kong regularly. It also encourages Chinese corporates to raise RMB funds and issue dim sum bonds in Hong Kong. In contrast, ever since the first RMB IPO in April 2011, there have only been a few exchange-traded securities in the offshore market. HKEx launched a deliverable CNH currency futures and dual currency listing of equity. There are also a few ETFs that pool offshore RMB and invest in the onshore securities market. However, these products are still at an embryonic stage.

| Figure 2: Hong Kong's RMB financing activities | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dim sum bond market | |||

| 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | |

| Issuance (RMB bn) | 116.0* | 122.2 | 107.9 |

| Outstanding (RMB bn) | 310.0 | 237.2 | 146.7 |

| Bank Lending | |||

| 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | |

| Outstanding RMB Loans

(*Estimate) |

115.6 | 79.0 | 30.8 |

| Source: HKMA, ANZ Research | |||

Singapore and Taiwan are catching up

Besides Hong Kong, the PBoC has also approved RMB clearing facilities in Taiwan and Singapore, both of which were also considered early movers in offshore RMB business. South Korea was one of the latest additions to the list of offshore markets with approved clearing facilities. Outside of Asia, London has been actively engaged in establishing offshore RMB business, and a RMB clearing bank was approved in 2014. The PBoC also approved a new clearing bank in Frankfurt recently, and further RMB clearing facilities are expected to be announced soon in Luxembourg and Paris.

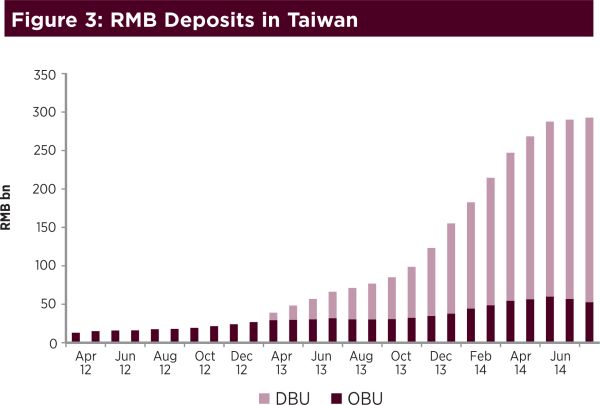

Taiwan started its RMB business in September 2011 in the offshore banking units (OBU). In February 2013, its domestic banks launched official RMB clearing by Bank of China Taipei, allowing local banks to tap the onshore liquidity. Different from the Hong Kong and Singapore model, there is also a Taiwanese bank operating in Shanghai to conduct New Taiwan dollar clearing. Total deposits held by the OBU and the domestic banking units (DBU) have grown rapidly and reached RMB292bn by the end of June 2014 (Figure 3). As there is no restriction or control limiting the inflows and outflows of the RMB, the so-called CNT exchange rate does not deviate from Hong Kong’s CNH.

Source: CBC, ANZ Research

We foresee an active RMB market in Taiwan. Many corporates will remit their onshore RMB to Taiwan through trade payments. Treasurers of many of Taiwan’s manufacturers find it convenient to manage their overall RMB positions, especially those who have both payables and receivables. Meanwhile, some fund managers are seeking regulatory approval to hold financial products linking to offshore RMB assets in other markets (ie Dim Sum). The higher yield of RMB-denominated assets compared with TWD is an attractive proposition of Taiwan’s wealth management industry.

On 7 March 2013, the PBoC and Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) doubled their local currency swap agreement to RMB300bn/SGD60bn. Two months later, Singapore began to offer RMB clearing, operated by ICBC Singapore. This official clearing channel is expected to promote the use of RMB by Southeast Asian companies and MNCs leveraging Singapore’s advanced financial infrastructure. From the beginning of the year to 8 April 2014, ICBC Singapore Branch RMB clearing volume reached RMB6.9 trillion, 2.7 times the volume for the whole of 2013. For the market as a whole, the size of total RMB deposits reached RMB220bn at the end of March.

For the RMB to become a global currency, its circulation in London is also viewed as critical. Given London’s dominant position in the FX market and the UK’s sizeable banking sector, the market potential for offshore CNY is enormous. London will allow the market participants to conduct RMB transactions more cost-effectively and securely on a global basis by allowing risk to be hedged and managed in the Western time zone. Basic RMB services are now available, including corporate CNH accounts, term deposits, loan facilities, FX services, treasury management, payment, cash management and trade financing. In 2014, China kicked off yuan-pound direct trading in the onshore interbank market.

London was seen to be active in dim sum bond issuance, taking full advantage of the strong Asian and European demand for exposure to CNH. In 2013, the Bank of England and the People’s Bank of China signed a bilateral currency swap agreement worth RMB200bn.

Trade settlements continue to drive RMB’s offshore circulation

The experience of the past few years suggests that trade remains the fundamental driver of cross border RMB flows and the key source for an offshore market to accumulate RMB liquidity. The experience of Hong Kong is a case in point. Prior to the inception of the trade settlement scheme in mid-2010, the volume of RMB deposits had only grown modestly, despite Hong Kong’s banking system launching personal RMB business in end-2004. Only after the clearing and settlement facilities were fully functioning in Q3 2010 did Hong Kong experience an explosive growth in RMB deposits.

Trade provides a natural way for an offshore entity to receive RMB payments. Naturally, China’s major trading partners will have more potential to develop RMB business and RMB banking.

A case of interest is Australia, which has been seen as the most active and high profile Western nation, with official blessing, encouraging the development of RMB business. Significant progress has been made. Firstly, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) signed a bilateral local currency swap agreement with the PBoC (AUD30bn / RMB200bn, three years, can be activated by either party) on 22 March 2012. In July 2012, the Australian Treasury, the RBA and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority planned to hold the first RMB Trade and Investment Dialogue in Sydney.

The most significant development was in April 2013, when the AUD/CNY pair started to trade in Shanghai’s interbank market with two Australian market-making banks (ie direct conversion), including ANZ. The daily fixing of AUD/CNY is no longer computed indirectly by the USD/CNY fixing and the global AUD/USD rate. Shortly after this direct conversion scheme, RBA deputy governor Philip Lowe said the RBA intended to hold around 5% of its foreign currency assets in RMB and had already gained approval from the PBoC.

We undertook a study which found that by removing USD from the conversion equation, businesses engaged in Chinese trade in Australia could potentially reduce the cost of FX volatility, expressed as 15% annualised gain in 30-day FX volatility. As the Chinese counterpart does not need to buy or sell a foreign currency (notably USD), Australian businesses could also negotiate better terms of trade with their Chinese counterparts.

However, even though China has already allowed for RMB trade settlement with all countries in the world since 2009, RMB is still rarely used in cross border trades, except those with Hong Kong. USD is still the most commonly used currency in China’s cross border trade. The reason is straightforward. A foreign party has no incentive to receive RMB because of its limited use in the offshore market and difficulty in repatriating it to the onshore market. This is still the most important bottleneck hindering scalable growth of the offshore RMB market.

Capital account restrictions begin to ease

To address this issue, the PBoC has started to launch a number of schemes promoting RMB capital account convertibility. In fact, China targets to have its RMB ‘basically’ convertible by 2015. This means that most of the items under China’s capital accounts will be allowed to flow in and out of the Chinese border (Figure 4). Allowing the inflows of RMB via the capital account will help complete the circle, increasing the incentive for offshore entities to receive or hold RMB.

| Figure 4: China's capital account convertibility | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of cross-border transactions | Not convertible | Partially convertible (highly restricted) | Basically convertible (light restriction) | Fully convertible | Total |

| Capital and money market transactions | 2 | 10 | 4 | - | 16 |

| Derivative and other instruments transactions | 2 | 2 | - | - | 4 |

| Credit instrument transactions | - | 1 | 5 | - | 6 |

| Direct investments | 0 | 1 | 1 | - | 2 |

| Liquidation of direct investments | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Real estate transactions | - | 2 | 1 | - | 3 |

| Individual capital transactions | - | 6 | 2 | - | 8 |

| Sub-total | 4 | 22 | 14 | - | 40 |

| Source: Statistics and Analysis Section, PBOC, February 2012 | |||||

Several schemes have been launched and piloted to facilitate the inflow and outflow of funds:

- RMB Outward Direct Investment (RMB ODI): In January 2011, the PBoC launched the Pilot RMB Settlement of Outward Direct Investment. A domestic institution can use RMB to fund its overseas acquisition of business ownership in the manner of formation, merger, acquisition or purchase of shares. In 2013, RMB ODI totalled RMB85.6bn, 1.8 times higher than in 2012.

- RMB Foreign Direct Investment (RMB FDI): In March 2011, the Ministry of Commerce launched the RMB FDI pilot scheme, allowing foreign investors to use RMB funds raised and acquired offshore for direct investment in China. In October 2011 the scheme was formalised. Although there are still a number of restrictions applied, this FDI scheme has seen substantial growth. In 2013, RMB FDI amounted to RMB448.1bn, an increase of 76.7% y/y.

- RMB Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (RQFII scheme): The RQFII scheme, which was launched in December 2011 to widen investment channels for overseas yuan funds on the Chinese mainland, allows qualified investors to invest their RMB funds raised in Hong Kong in the mainland securities markets within a permitted quota. While the scheme was initially targeted at onshore bonds investments, it kept evolving. The China Securities Regulatory Commission allows institutions under the RQFII programme to issue exchange-traded funds (ETFs) made up of A-shares.

As of July 2014, the total approved quota of RQFII reached RMB257.6bn (Figure 5). On 2 May 2013, the PBoC issued a notification detailing the operational procedure and administration of the RQFII. This RQFII administrative rule will serve as a model signifying a basic completion of liberalisation of capital accounts on an institutional basis.

Source: CEIC, ANZ Research

- Cross-border inter-company intra-group RMB lending: In November 2012, the PBoC approved the first RMB cross-border loan quota of RMB3.3bn to a commercial bank. The approval was part of a pilot scheme to allow foreign companies in Shanghai to lend RMB surplus overseas. The two parties can agree on the interest rates directly.

- Automated Foreign Currency Sweeping Structure: The State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) launched a pilot scheme for Chinese SOEs, multinational corporates, and foreign banks to sweep their non-RMB holdings from their onshore accounts in China to offshore accounts.

- Individual cross-border transactions backed by local financial sector reform: Yiwu, a city in Zhejiang province, is piloting a financial sector reform that will encourage the use of RMB in cross-border trade and capital transactions by exporters/importers, freight forwarders and individual business acquisition parties.

It will reportedly liberalise the flows for cross-border business acquisitions which are currently subject to a limit of USD50,000 per year.

On 19 April 2013, Fujian province issued a policy framework promoting a financial service reform for Quanzhou. The plan will reportedly promote a closer engagement between local banks and Taiwan’s banks for offshore RMB business. It also plans to develop bilateral and reciprocal RMB lending with Hong Kong.

In July 2012, Qianhai, a district within Shenzhen, launched a high profile campaign promoting financial integration with Hong Kong. It has issued detailed rules to accelerate bilateral cross border lending with Hong Kong.

Earlier in March 2012, the State Council approved the establishment of a special zone for Wenzhou’s financial comprehensive reform, which encouraged a more vibrant use of private-sector capital and examined the possibility of outward foreign direct investment using RMB.

Going forward, we expect liberalisation will shift to individual cross-border flows, commonly labelled as QFII2 (inflows) or QDII2 (outflows). This will encourage freer flows of personal wealth to overseas markets. Using RMB for individual trade transaction will also promote easier cross-border online shopping. This will be an important step for China’s e-businesses to expand their overseas markets.

Our core view remains that the ongoing capital account liberalisation will propel a convergence of onshore and offshore RMB interest rate as offshore entities will be allowed to use the RMB funds raised offshore for onshore business acquisitions, portfolio investment and working capital needs. Likewise, RMB outward investment scheme in designated trial zones may facilitate an easier outflow of the RMB for offshore transactions. As the interest rate differential narrows, the CNY and CNH exchange rates should also draw closer.

Challenges ahead

There are some near-term and medium-term challenges facing the RMB’s internationalisation process.

In the near term, the authorities will have to strike a balance between the pace of RMB internationalisation and the monetary authority’s ability to absorb a large wall of money owing to the quantitative easing policies undertaken by the US Federal Reserves and more recently and aggressively, the Bank of Japan. To facilitate RMB’s internationalisation, the authorities have allowed engaging in fast capital account liberalisation with an aim to reducing the barriers of capital movements. Large onshore and offshore interest rate differentials will draw large capital inflow as well, thus potentially inflating the property bubble further, rendering the monetary policy ineffective, and sowing the seeds for a financial crisis.

In the medium term, whether the international community will accept the RMB as a global currency in trade and finance also hinges on the sophistication of China’s financial markets. In particular, China’s domestic financial liberalisation will have to move forward. At this stage, China is still engaged in financial repression with interest rate control, homogenous state ownership, and limited competition. The current financial system favours the state-owned enterprise sector at the expense of China’s more dynamic private sector. SOEs are often fed with a large amount of credit disproportional to their contribution to the economy.

In addition, the lack of competition in the financial system also means interest rate liberalisation will lead to higher interest rates, defeating the very purpose of interest rate liberalisation. Therefore, China will need to have a careful sequencing strategy to domestic financial liberalisation by allowing fast ownership diversification of the financial system to enhance competition and efficiency, interest rate liberalisation, and encouraging large and listed companies to tap into the debt capital markets. Furthermore, a flexible exchange rate system is needed with a more open capital account. Otherwise, persistent interest rate differentials will propel large capital flows that may affect the overall monetary and financial stability.

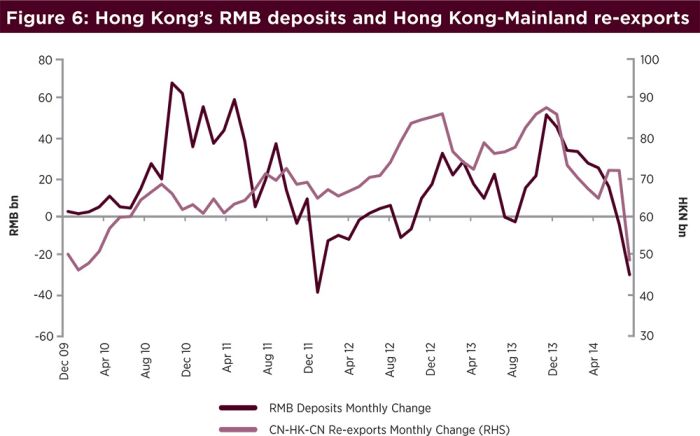

Indeed, the surge in cross-border trade flows for financial gains underscores this point. Last year, the problem of capital flows via the channel of RMB trade settlement increased rapidly (Figure 6). Through round tripping of goods and over-invoicing, the non-genuine trades become a loophole for bringing ‘hot money’ into China. The improper use of the cross-border trade settlement in the RMB to mask capital flows has triggered the recent tightening by the SAFE on banks’ trade-related transactions and FX exposure. While the tightening measures have taken effect to a certain extent, we think that this type of administrative measure fails to fix the root problem, that is, the large interest rate differential and one way bet on RMB’s appreciation with little volatility, which acts as a major attractor for capital inflows.

To conclude, the RMB’s internationalisation is a gradual process, requiring a careful sequencing strategy of domestic financial liberation and capital account opening. The current strategy of the RMB internationalisation is to first encourage the currency to be used as a trade invoicing currency and then as a trade financing currency. Once the offshore RMB liquidity becomes large enough, the RMB-denominated financial products have become rich, and the markets have become sizeable, the RMB will become a global currency. With Shanghai’s ambition to become a global RMB trading and settlement centre in 2015, the RMB will likely become a basically convertible currency, which will pave the way for it to become a major global currency by 2020.