An introduction to equity capital

| Corporate finance | |

|---|---|

| |

| Authors | |

|

10 Upper Bank Street, London, E14 5JJ Switchboard: +44 (0)20 7006 1000 Fax: +44 (0)20 7006 5555 |

Introduction

This article provides an overview of the key features of equity financing in a general context. For detail on equity financing in specific jurisdictions, please refer to the relevant Country Guides.

Equity capital

A company’s equity capital is that part of its capital which reflects the residual value of its assets after taking account of all third party liabilities. The equity capital in a company in liquidation is the property of the holders of ordinary shares hence these shares are often referred to as equities.

Equity shareholders have a right to share in the profits of the company or any surplus assets on winding up. In accordance with legislation and accounting standards, shares in a company’s share capital may usually be either equity shares or non-equity shares. Broadly what distinguishes an equity shareholder from a non-equity shareholder is his/her right as regards dividends and as regards capital. An equity shareholder has the right to participate in a distribution and share in any surplus assets on a winding-up beyond a specified amount.

Equity instruments

Generally a company’s ordinary shares are those with which it is incorporated and where a company has only one class of shares that class will be ordinary shares. Ordinary shares typically carry rights to vote on all matters put to a general meeting of a company, rights to dividends and rights to participate in a surplus on a winding-up.

A company may, however, create different classes of ordinary shares with different rights as to voting or dividend or other rights such as the right to appoint a person to the board of directors. Once ordinary shares are fully paid, a shareholder has no further liability on his/her shares. In a winding up of the company, an ordinary shareholder will rank behind secured creditors and behind holders of any other class of share to which his/her rights have been subordinated in the articles of association.

A company may create “preference” shares, which have a preferential right in respect of income or capital (or both) over the ordinary shares in a company. Preference shares do not necessarily confer preferential treatment in other respects and the precise rights attaching to the shares will usually be set out in the company’s articles of association. The types of rights a company may attach to preference shares include dividend rights, capital rights, limited voting rights, conversion rights and redemption rights.

Preference shares are often issued on terms that provide for a dividend payable annually or at the end of every six-month period. Where the preference shares provide for a preferential right in respect of a dividend, the dividend is prima facie cumulative so that the dividend is rolled up and any outstanding unpaid or undeclared dividend becomes payable in priority to a dividend on ordinary shares when distributable profits become available.

The dividend may be automatically declared so that it will become a debt due from the company on its due date without further action on the part of the board or shareholders provided that the company has sufficient distributable profits.

Preference shares typically carry a priority right to dividends (usually limited to a specified percentage per annum) and a return of capital (usually limited to the amount paid upon those shares plus any accrued but unpaid dividends), but do not qualify to participate in any ordinary dividend or surplus on a winding up. Such shares constitute non-equity capital for the purposes of the UK companies’ legislation.

Convertible and exchangeable bonds

A convertible bond is a debt security issued by a company which, during a period between the issue date and the maturity date, can be surrendered by the holder in exchange for shares in the capital of the same company that issued the bond. An exchangeable bond differs only in that the bond is exchangeable for shares in a company other than the company issuing the bond.

Generally, the issuer of an exchangeable or convertible, as for any other bond, agrees to pay an interest coupon and to repay the principal at maturity. Upon conversion or exchange by a holder, the principal amount of the bond is applied in subscribing for shares at a conversion price that is fixed (subject to adjustment in certain limited circumstances) at the time of issue of the convertible bond. The conversion price is the amount of the face value of the bond that must be surrendered for each share received on conversion.

Investors in exchangeable/convertibles typically agree to an interest coupon at below-market rates in return for the potential upside if the market value of the shares appreciates in value. On the other hand, issuers potentially give up some equity in exchange for the lower funding cost. The conversion price at which the bonds are convertible into shares is normally established at a premium (the conversion premium) to the issuer’s share price at the time of issue. The amount of the premium is a matter of negotiation between the issuer and the lead managers of the issue.

Typical features of convertible bonds include:

- adjustment provisions – the conversion price usually does not change over the life of the bond except to the extent that it is adjusted pursuant to anti-dilution provisions designed to protect the value of the conversion/exchange right in certain circumstances including rights issues, share splits and capital distributions;

- issuer call (often referred to as a “soft call”) – allowing the issuer to redeem the bonds at a fixed price at a future date if the market price of the underlying shares exceed the initial conversion price (usually by 130% to 140%) over a specified period thereby forcing holders to convert/exchange and realise the appreciation in the share price; and

- bondholder put – allowing the holder to choose to have the bonds redeemed at a pre-determined level at a fixed future date. The put price is typically at a premium so that, on exercise, the holder will receive a yield equivalent to a straight bond issued by that company.

Warrants

Share warrants are securities entitling the holder to purchase from the issuer, at a stated exercise (or strike) price, which is fixed on issue, the underlying shares of the company issuing the warrants at any time prior to their expiration. Warrants may be exercisable on a stated date during the life of the warrant (European style) or on any day in a fixed period (American style). Warrants have often been used by companies (particularly weaker credits) as a “sweetener” attached to bonds to improve their marketability.

Although warrants are similar to convertibles in that they give investors an opportunity to participate in capital gains in the shares, there are a number of key structural differences. Unlike a convertible or exchangeable bond, where the conversion right is simply one of the terms of the instrument, warrants can be traded as separate securities. Furthermore, a warrant does not itself help to eliminate debt or reduce fixed debt service costs since no bonds are redeemed when the warrants are exercised. However, unlike a convertible, which simply involves one security being exchanged for another, a warrant does produce a cash inflow into the company at the time the warrant is exercised.

Warrants usually have a limited life, and the exercise price will be fixed at a premium to the market price of the shares at the time the warrants are issued. Consequently, if the share price does not rise above the exercise price, the warrant will never be exercised. The exercise ratio specifies the number of shares that can be obtained at the exercise price with one warrant. For example, if the exercise ratio on a warrant were 2.0, one warrant would entitle the holder to purchase two shares at the exercise price.

Equity issuance

Bonus issues

Bonus issues are issues of shares by a company to its members, the subscription price for which is met by the company capitalising its reserves.

Bonus issues allow the share capital of a company to be increased without further cash or assets being introduced.

Scrip dividends

A company may decide to give its shareholders the choice of taking a dividend either in cash or, as an alternative by way of “Scrip” whereby a shareholder may elect to take shares in respect of all or part of what would otherwise be his/her cash dividend entitlement. In the case of a listed company, the price of the new shares will normally be based upon the average market price of the existing shares of the company over the five dealing days following the ex dividend date. In the case of an unlisted company another means of valuation will be required. A shareholder electing to take shares will also receive a balancing payment to ensure that he/she receives the full dividend entitlement.

A listed company which gives the choice of a scrip dividend alternative will send a circular to its shareholders setting out the terms of the issue. Companies sometimes set up a permanent scrip dividend scheme under which a shareholder gives a mandate to the company to issue it with shares rather than cash each time a dividend is declared until it gives notice to the contrary. This has cost, cashflow and administration advantages for a company that regularly pays interim and final dividends and has a large shareholder base.

Pre-emption rights

Before issuing new securities, a company should consider whether there are any pre-emption rights conferred on existing shareholders, either by statute, regulation or by the company’s constitutional documents. On a new issue of securities, pre-emption rights provide that existing shareholders may subscribe for further shares pro rata to their existing holdings.

In broad terms, the protection of the priority rights of existing shareholders to subscribe for further share issues, and the ability to sell those rights, give shareholders the chance to ensure that the value of their individual interests are preserved.

UK equity finance

Introduction

There are various way in which a company may raise equity finance. In the UK, the most common means by which a listed company may raise equity finance are by way of a rights issue, open offer or placing of shares. The first two methods are pre-emptive in nature and ensure that existing shareholders, should they chose to participate in the offer, are able to maintain their pro rata holding of shares in the company. A placing of shares is a non pre-emptive offer of shares. The shares may be offered to selected existing shareholders or new investors may be targeted by a company. A company may chose to utilise more than one of these methods at the same time and could, for example, combine a rights issue or an open offer with a placing of equity shares. The key features of these types of share offers are discussed below.

| Rights issues |

|---|

|

Any premium over the offer price obtained in the market will be paid (net of expenses) to the shareholder who was originally offered, but declined, the new shares or to the person to whom that shareholder renounced his/her rights. The price of the shares or other securities to be issued pursuant to the rights will be set at a discount to market value in order to assist take-up (see “Theoretical ex-rights share price and value of a right” below).

A listed company will usually have the rights issue underwritten in order to ensure certainty of funds (see “Underwriting” below for further details). An alternative to this is however to offer the shares at a deep discount to market price (e.g. 40% to 50%) to achieve a similar effect. More usually however, even where companies have launched deeply discounted rights issues they are also underwritten. To reduce underwriting expenses, a company may seek irrevocable undertakings from some of its larger shareholders to take up their entitlement to shares under the rights offer, thereby reducing the number of shares which are required to be underwritten.

Rights issues have historically been associated with fund raising in challenging conditions and the financial crisis in 2008/2009 saw a significant peak in rights issues as companies sought to raise funds to pay down debt. After 2009, the number of rights issues declined but since 2012, they have become increasingly common, with 2014 seeing double the number of rights issues that took place in 2013, with over half of those undertaken in 2014 being to raise cash to fund an acquisition. By way of example, the largest rights issue in 2014 was that undertaken by Babcock International Group plc, which raised £1.1bn in order to part fund the acquisition of Avincis.

- Theoretical ex-rights share price and value of a right – as mentioned above, a rights issue gives existing shareholders the right (but not the obligation) to purchase a number of new shares calculated by reference to an existing holding at a given price (the issue price). For example, a one-for-four rights issue at £10 gives the shareholder the right to purchase one new share at a price of £10 for every four shares already held. A share that has the right to purchase the new shares attached is known as a cum-rights share. When the rights are admitted to listing and trading they are effectively detached from the existing ordinary shares as they may be traded separately. As such, the existing ordinary shares are marked ‘ex’ by the London Stock Exchange, reflecting that those shares are then traded ex-rights.

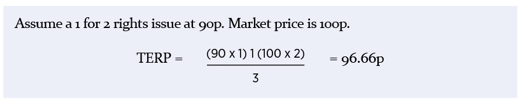

In a perfect market, the only difference between the cum-rights price and the ex-rights price would be the value of the right to subscribe to the issue. The theoretical ex-rights price (TERP) of the shares once they are marked “ex” is calculated as follows:

This formula is used as an estimate and guide to establishing an appropriate discount when pricing a rights issue, based on a perfect market with no external influences. In reality there are many other factors that could cause the TERP to vary considerably from the calculation derived from this formula.

Open offer

An open offer is, in many respects, like a rights issue. It is an offer to existing shareholders to subscribe in cash for new shares or other securities in a company, pro rata to their existing holdings. Unlike a rights issue, however, there is no allotment of nil paid rights which are tradeable during the offer period. Shareholders must take up and pay for the securities offered to them under the open offer, failing which the offer lapses at the end of the offer period.

It is possible to build in a compensatory element to an open offer whereby the open offer shares not taken up by shareholders are placed at the end of the subscription period for the benefit of those shareholders who have not taken up shares under the offer if a premium over the subscription price can be obtained (this is standard practice in a rights issue). This type of “compensatory” open offer was used in the Lloyds Banking Group 2009 placing and open offer but it is not market norm.

The Financial Conduct Authority’s Listing Rules restrict the discount at which open offer shares may be offered to 10% of the “middle market price” of those shares at the time of announcing the terms of the offer or when the offer is agreed. The middle market price of equity shares means the middle market quotation for those shares as derived from the daily Official List of the London Stock Exchange on the relevant date. The discount prohibition does not apply to an open offer at a discount of more than 10% if the terms of the offer at that discount have been specifically approved by the company’s shareholders.

Like a rights issue, an open offer will usually be underwritten in order to ensure certainty of funds. Irrevocable undertakings may be sought from a company’s key institutional shareholders to take up their shares under the open offer in order to try and reduce underwriting costs.

Placings

A placing of equity shares generally involves a non pre-emptive issue of new shares for cash to new and/or existing investors (known as “placees”). Existing shareholders who are not invited to participate in the placing will see their shareholdings diluted as a result. Any such issue by a UK-incorporated company will be subject to the pre-emptive provisions of the UK Companies Act 2006.

Subject to obtaining the necessary shareholder consent, a company is permitted to disapply the statutory pre-emption provisions. However, listed companies are further restricted in their ability to disapply pre-emption rights by the guidelines issued by the Pre-Emption Group which represents the institutional investor community. In March 2015, the Pre-Emption Group published an updated Statement of Principles (the 2015 Statement) which sets out the Group's views on the disapplication of pre-emption rights by premium listed companies and issues of shares for cash on a non pre-emptive basis.

The general principle is that a listed company's annual resolution to disapply statutory pre-emption rights should be restricted to an amount of equity securities not exceeding 5% of the current issued ordinary share capital. The 2015 Statement introduces a new flexibility which enables companies to seek a disapplication for up to a further 5% of issued ordinary share capital for use in connection with either an acquisition or a specified capital investment. In the AGM circular at which this additional flexibility is sought, the company should make clear its intention to use the additional 5% only in connection with an acquisition or specified capital investment which is either announced contemporaneously with the issue or which has taken place in the preceeding six-month period and is disclosed in the announcement of the issue.

The 2015 Statement also seeks to restrict the total number of equity securities issued for cash on a non pre-emptive basis in any rolling three-year period to 7.5% of issued ordinary share capital.

The result is that a listed company is able to place only limited numbers of shares without further recourse to shareholders. Placings involving larger amounts will require additional shareholder approval to disapply pre-emption rights. Institutional investors are to be more likely to grant their consent if the placing shares are offered to shareholders on a “clawback” basis. This involves the placing shares being placed with placees on launch, then offered to existing shareholders, with shares being clawed back from placees to the extent shareholders take up their shares.

The Financial Conduct Authority’s Listing Rules also require that where a listed company makes a placing of equity shares the price must not be at a discount of more than 10% to the “middle market price” of those shares at the time the placing is agreed. The discount prohibition does not apply to a placing at a discount of more than 10% if the terms of the placing at that discount have been specifically approved by the company’s shareholders.

Additionally, the 2015 Statement seeks to further restrict the discount at which a listed company may issue equity securities for cash other than to shareholders, to a maximum of 5% of the middle market price immediately prior to the pricing of the issue.

Market practice varies regarding underwriting. Depending on the expected level of demand for the shares, a placing may or may not be underwritten.

Timing and use of funds

A placing is generally the quickest means of raising equity capital. A placing is generally structured to ensure that there is no requirement for either shareholder approval to be obtained or for a prospectus (that is, an offering document which must include prescribed information about the company and the securities being offered) to be prepared. In such cases, a placing can usually be concluded, and a company in receipt of the placing funds, in less than five business days from launch.

A rights issue or open offer will take longer to conclude. The offer must be held open for two weeks, but the timetable will be further extended by the need to prepare a prospectus. In addition, if shareholder approvals are required, these may further extend the timetable.

The application of the proceeds of any such offer of equity securities will vary from issue to issue. Common uses of funds include the repayment of borrowings to lower a company’s gearing ratio, assisting working capital requirements and the financing of an acquisition.

Underwriting

A company will usually seek to have a securities issue (whether by means of a rights issue, open offer or other type of offer) underwritten in order to ensure certainty of the amount of funds raised. This is very important where the purpose of the issue is to provide funds to meet specific financial commitments. The issuer will enter into an agreement with an underwriter or a syndicate of underwriters and will agree to pay a commission to the underwriters, which is usually expressed as a percentage of the total funds intended to be raised.

The underwriters’ obligation to underwrite will be conditional on various matters including the admission of the relevant securities to listing and trading. The underwriting agreement will normally contain an indemnity given by the company to the underwriters and warranties given by the company and, possibly, the directors, to the underwriters in relation to the company’s business at the date of the agreement and immediately prior to admission of the securities to listing and trading.

The underwriters will retain the right to terminate their obligations prior to admission where a warranty is breached and will commonly seek a force majeure clause which allows them to terminate the agreement prior to admission if there is an international or domestic event (usually linked to economic or market conditions or an outbreak of hostilities) that they believe justifies the withdrawal of the issue.

The economic downturn saw an increased focus by underwriters on their ability to terminate underwriting arrangements. This led, in some transactions, to the inclusion of provisions that would allow an underwriter to terminate the underwriting in very specific circumstances; for example, the downgrading of an issuer by a credit rating agency.

Once the terms of the underwriting arrangements are agreed, the underwriter will usually seek to lay off some or all of its risk to sub-underwriters to whom it will pass on some of the commission it is receiving from the company.