Sharia-compliant fixed income capital markets instruments for cross-border transactions

| Corporate finance | |

|---|---|

| |

| Authors | |

| Debashis Dey | Partner, Global Capital Markets Practice |

| Claudio Medeossi |

Counsel, Global Capital Markets Practice White & Case LLP |

Introduction

Generally known by their Arabic name, sukuk, and often incorrectly referred to as ‘Islamic bonds’, Sharia-compliant fixed income capital markets instruments have steadily increased their share of global markets over the last decade. Initially developed exclusively in jurisdictions with majority Muslim populations, the global market for sukuk has seen considerable development over the last decade, with a number of high-profile corporate issuances and a number of sovereigns tapping the market. This trend has been generating increasing interest in the global sukuk market as an alternative and growing investor base, which has culminated recently in 2014 with sovereign issuers such as the United Kingdom, Luxembourg, Hong Kong and the Republic of South Africa all having used them.

Sukuk are financial products whose terms and structures comply with Sharia, while intending to produce financial returns that are similar to those of conventional fixed income instruments like bonds. Unlike a conventional bond (secured or unsecured) which represents the debt obligation of the issuer (ie a promise to pay interest on a scheduled date at a defined rate, together with the repayment of the capital on a defined date or dates), a sukuk technically represents an interest in an underlying funding arrangement structured according to Sharia, entitling the holder of a sukuk certificate to a proportionate share of the returns generated by such arrangement and, at a defined future date, the return of the capital.

Broadly speaking, compliance with Sharia means: (i) that any profits derived from these funding arrangements must be derived from commercial risk-taking and trading only, (ii) all forms of conventional interest income is prohibited, and (iii) the assets which are subject to the funding arrangement must, themselves, be permissible (halal). Notwithstanding the foregoing, in today’s typical sukuk transactions, the overall risk profile and economic return for the investor is akin to a conventional bond where the bondholder is a debtor of the issuer.

Types of sukuk

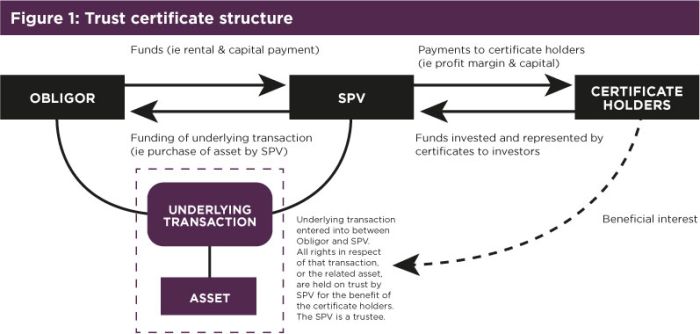

The sukuk that have been issued in the global capital market have been predominantly structured as trust certificates, typically governed by English law. Some civil law jurisdictions that do not recognise the concept of trust have sometimes issued sukuk structured as participating notes under bespoke domestic legislation based on, or similar to, that used for asset-backed securities.

Trust certificates

In a typical trust certificate transaction, the entity trying to raise funds (hereafter referred to as the ‘Obligor’) will establish an orphan, offshore SPV (Special Purpose Vehicle) in a suitable jurisdiction. The SPV issues the trust certificates to investors and uses the proceeds to enter into a funding arrangement with the Obligor and the rights of the SPV as financier under such arrangements as are held under an English law trust in favour of the certificate holders.

The funding arrangement can be structured in several ways. The Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) – an Islamic international autonomous non-for-profit corporate body that prepares accounting, auditing, governance, ethics and Sharia standards for Islamic financial institutions – has identified and issued standards for various different structures for the funding arrangements which can underlie a sukuk. In recent years there have been several attempts to standardise documents for these funding arrangements and provide platforms for predictability and industry norms in the form of AAOIFI guidelines and International Islamic Financial Market (IIFM) templates. In addition, the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) and organisations such as the International Islamic Liquidity Management Corporation (IILM) and the Gulf Bond and Sukuk Association (GBSA) are also seeking to facilitate the standardisation of innovative product structures. The structures most common in the Islamic market include a sale and leaseback (ijara) structure, a form of trade finance (murabaha) and a joint-venture equity investment (musharaka).

The holder of the trust certificates is entitled, pursuant to the trust, to share the returns generated by such underlying funding arrangements. Though structured as a beneficial entitlement to a pool of assets (ie the rights of the financier under the funding arrangement), a trust certificate structure, in many senses, aims to replicate the financial performance and investment risk of a typical unsecured senior Eurobond, and generally contains features (such as negative pledge and events of default) akin to those of similar fixed-income investments.

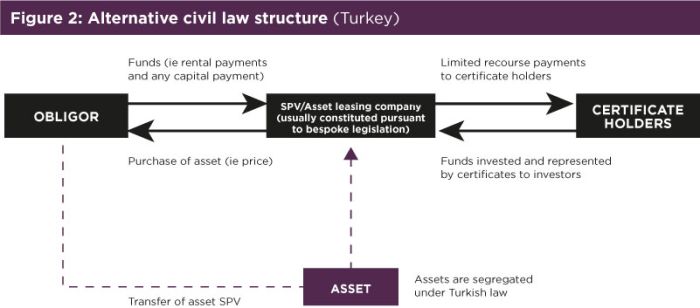

Alternative civil law structures

The trust certificate structure above requires the concept of a trust to be recognised in the relevant jurisdiction where the Obligor is located. In many jurisdictions, particularly those from the civil law tradition, this is very rarely the case. As such, alternative structures have begun to emerge so as to allow for sukuk transactions to be carried out in accordance with local laws.

An interesting example of such a trend is exemplified by the Republic of Turkey, which has passed specific legislation to enable the use of the sukuk. This legislation allowed for the formation of asset-leasing companies, which themselves are a form of SPV regulated by the Capital Markets Board of Turkey. These asset-leasing companies are specifically incorporated so as to be able to issue certificates under an ijara structure to investors, thereby allowing the asset-leasing companies to purchase assets and lease them back to the Obligor. Effectively, the asset-leasing company finances the acquisition of such assets using funds raised by the issuance of certificates and the lease rental payments from the Obligor mirror the profit distributions due under the certificates. The cash flows from the lease rentals, therefore, are used to service such profit distributions to certificate holders.

This model is best compared to loan participation notes (LPNs), which have been in the market for several decades. Similar to the Turkish sukuk described above, the LPNs involve the creation of an SPV, which issues notes into the capital markets and immediately on-lends the proceeds to a borrower. As with the Turkish sukuk, the LPN investors’ recourse to the SPV is limited to the amounts actually received by the SPV from the borrower in the form of interest and capital repayments.

The economic benefit and risk of the structure: investors’ credit exposure

Despite the fact that the sukuk is issued by an orphan SPV, typically the investor will not be bearing an exposure solely to the credit risk of that SPV. On the contrary, today’s typical sukuk transactions are instead primarily intended to allow the investor to be exposed to the credit risk of the Obligor. However, the key question a potential investor needs to consider is whether the sukuk is giving the investors only recourse to the Obligor, or also to a separate segregated estate represented by the assets subject to the funding arrangement underlying the sukuk. In the current sukuk market, the answer to this fundamental question may not always be obvious.

For example, where the underlying funding arrangement is an ijara, certain assets are intended to be transferred to the SPV, which will then lease these assets back to the Obligor. Given this transfer of assets, it may seem that a sukuk based on an ijara structure offers the investors full recourse to the assets so that, in the event of a default, the investors can either liquidate the assets or lease them to a different lessee. However, typically, in most sukuk transactions based upon an ijara, the transfer of the asset does not achieve this result as a legal matter, and the investor only has recourse to the general insolvency estate of the Obligor, rather than the asset that was supposedly transferred.

Understanding the real nature of the connection between the funding arrangement and the asset to which it relates is central to understanding the economic risk of the sukuk and its risk allocation. It is therefore important for a potential investor to know whether the asset underlying the funding arrangement has been permanently transferred to the SPV. Either the investor will have legal recourse to the underlying asset (what is generally referred to as an asset-backed sukuk) or, alternatively, even though the transfer of the asset may be valid as between the Obligor and the SPV, the investor only has recourse against the Obligor because that transfer is not effective as against third parties or the insolvency estate of the Obligor (what is generally referred to as an asset-based sukuk).

Asset-based vs asset-backed

In an asset-based sukuk structure, the overriding reliance of investors is on the credit strength of the Obligor rather than on the underlying assets. This allows the Obligor to simplify its reporting and segregation in relation to the assets, as the Obligor knows that the investors are really relying on the Obligor’s credit strength alone.

For example, in an ijarah transaction, where there is a sale by the Obligor of an underlying asset to the SPV that will then be leased to the Obligor, if the sukuk is structured as a typical asset-based structure it becomes irrelevant for an investor to fully analyse the sale value of the asset in question or the potential value of the lease if leased to third parties, as the investors will rely only on the credit strength of the Obligor as sole or principal lessee of the asset in question.

Where the structure involves an obligation extended by the Obligor to repurchase the asset in case of financial default by the Obligor, or where the sukuk has reached the date by which capital is scheduled to be fully returned, the investors will, through the actions of the SPV holding the assets for the investors, ‘put’ the asset to the Obligor, thus crystallising the debt claim against the Obligor for the capital amount equal to the outstanding sukuk capital (for more information on the purchase undertaking, please see Documentation section below).

In an asset-based structure, the investors would likely be keen to investigate the strength of the balance sheet of the Obligor to quantify the credit strength as sufficient to make the relevant payments required by the underlying transaction (and thus ultimately return capital and generate income for the certificate holders). What the investors do not need to do is review the assets on an independent basis as if they were genuinely acquiring the assets as owners and then assessing what rental income could be derived from leasing them in the open market or what could be obtained from selling the asset on the open market.

In an asset-backed sukuk, the profit return and return of capital are ultimately based on the assets themselves. Unlike the asset-based structure, investors can be expected to want to try to assess the value of the assets (and the related underlying transaction) for themselves. Thus, for example, in the ijarah structure described above, if the transfer of the assets was structured as permanent transfer under the relevant contracts, in the case of a default by the Obligor the investors would have recourse also to the asset value of both the asset itself and the value of any lease that could be genuinely obtained in the open market. Given that the investors’ return would ultimately depend upon the asset and the value of any lease, there would have to be a critical analysis of the asset and most likely a discounting of such value to provide some cushion in case there are unforeseen market events that affect future value.

Although asset-backed structures seem to better reflect the views of the scholars, the current market has not yet seemed to embrace that model, and in the global market the majority of the sukuk are currently asset-based. This seems to be primarily due to the fact that there does not seem to be an appetite from either the investors or the Obligors for an asset-backed approach. From the perspective of the investor, investors do not appear to wish to invest in the resources necessary to properly assess asset values, as the assessment of an asset at the time of purchase requires dedicated knowledge of the industry in question, the market generally, and the ability to compare such asset value to other similar historic asset purchases. From the perspective of the Obligors, the concept of an asset sale that leads to recourse against the assets in a default appears to be beyond their current appetite for funding, particularly if they are comparing their funding options against a conventional bond or loan that does not have the same features. In addition, the idea that the sukuk investors can sell the assets to third parties in an asset-backed structure will often practically limit the assets the Obligor wishes to make available for the sukuk.

Delegate/representative

Similarly to bonds, sukuk can be structured in order to provide investors with a form of collective representation akin to that provided by trustees in the Eurobond market.

In a trustee SPV model, a separate entity – generally called a delegate or a representative – is given certain powers for the benefit of the investors. These powers include the authority to agree amendments to the transaction documents in certain circumstances (ie in order to cure of manifest error or if the amendment is formal or technical or it is not materially prejudicial to the interests of the certificate holders), to grant waivers, to appoint replacement trustees, to convene meetings of the certificate holders and to bring a claim against the Obligor on behalf of all the certificate holders. Where the sukuk is structured using the trust certificate model (where the SPV is the trustee of the certificate holders), this role will also include a delegation of the rights of the SPV against the Obligor. The main reason for this is that the SPV in a sukuk transaction is an orphan SPV, the directors of which will often be unwilling or unable to perform a role as sophisticated as would be required of the delegate/representative. The end result is a role akin to that of a bond trustee in a conventional bond transaction and is normally performed by professional corporate finance trustee companies. The structuring of this role depends mainly on how an Obligor wishes to deal with its investors over the life of the transaction.

The pros and cons of using this model will depend largely on the context of the transaction, but from the perspective of the Obligor, in the case of a default, the delegate/representative model allows for the concept of communal action (akin to that of bondholders acting through a trustee). Though this creates the possibility of class action by the investors against the Obligor, this has the benefit to the Obligor that any action to enforce rights against it must normally be voted on by a majority of certificate holders. Furthermore, from the perspective of the certificate holders, having a professional trustee acting in the role of delegate/representative means that they are protected by the fiduciary duties afforded to them under English law.

Documentation

Sukuk transactions are largely documented in the same way as a typical Eurobond transaction, with the exception of the added documentation of the underlying Islamic funding arrangement. For the purposes of this wiki, set out below are the typical documents seen in a sukuk that is based on an ijara structure.

Capital markets documents

- Prospectus: As with a conventional bond, this can also be referred to as the offering circular or information memorandum. The prospectus will contain the level of disclosure usually required for conventional bond issuances, and may include details of the pronouncement by the relevant Sharia board or authority applicable to the certificates and underlying transactions.

- Subscription agreement: this is in the usual form used for conventional bond issuances.

- Document creating the trust and constituting the trust certificates: in a trust certificate structure, there will be a document in which the SPV will declare a trust for the benefit of the certificate holders over all its rights in respect of the underlying funding arrangement (and related assets). It will also be the instrument in which the certificates are constituted and may contain the forms of the certificates themselves and their terms and conditions. It is also in this document that the delegate/representative is appointed, its powers are granted, and the SPV delegates the performance of certain duties, powers, authorities and discretions vested in the SPV by the relevant provisions of the trust document.

- Paying agency agreement: this is in a similar form to that used for conventional bond issuances.

Islamic funding documentation

- Transfer agreement: entered between the SPV and the Obligor, under this contract the SPV will purchase the assets which it will then hold on trust for the benefit of the certificate holders.

- Purchase undertaking: entered into by the Obligor in favour of the SPV, the purchase undertaking is the mechanism by which the assets will be transferred to the Obligor at maturity so that the certificate holder is repaid its capital. The purchase undertaking is also the mechanism by which investors’ rights are enforced upon an event of default, as it contains provisions to be exercised by the delegate/representative (in the trust certificate model), or otherwise by the SPV, which forces the Obligor to buy back the assets.

- Lease agreement: the agreement, entered into between the SPV and the Obligor, is the mechanism whereby the assets are leased to the Obligor so that the lease payments will match the periodic payments due to the certificate holders under the trust certificates. In order to comply with the allocation of risks required for the ijara transaction to be Sharia-compliant, the SPV (ie the lessor) is responsible for: (i) some maintenance and structural repair, (ii) any taxes related to the asset(s), and (iii) total loss insurance. In practice, the responsibilities of the SPV are assigned to the Obligor under the servicing arrangements. The Obligor will normally be responsible for the performance of all ordinary maintenance and repair required on the assets during the term of the rental period, in the capacity of a servicing agent of the SPV.

- Servicing agreement: the Obligor is typically appointed by the SPV as the servicing agent to collect rents and perform maintenance and repairs.

Pricing

Sukuk certificates may carry either a fixed or a floating profit margin. Pricing is primarily a function of the credit standing of the Obligor and of market conditions.

The credit rating of the Obligor is important in determining the potential pricing range of the sukuk certificate. In addition to credit ratings, factors such as industry sector and name recognition play an important part in determining pricing.

Whereas generally for fixed-income products the pricing and trading activity within a secondary market is key to pricing, the fact that the secondary sukuk market is fairly small means that this reference point for pricing is unlikely to be available for sukuk certificates.

Advantages and disadvantages of sukuk

Advantages

For a corporate or a sovereign, some key advantages of tapping the sukuk market include:

- There is a potential marketing benefit for issuers active in Islamic markets, should they be seeking investments in those markets.

- The investor base represented by Islamic compliant investors is still largely untapped, and there has traditionally been significant unmet demand for products like sukuk.

- There is potential for crossover into other niche financial markets, such as the broader ethical investment market, which may provide a reputational benefit.

Disadvantages

Some disadvantages of the sukuk market include the following:

- As the key element for attracting investors is the credit standing of the Obligor, it may be difficult to tap this market for corporates or sovereigns with an inadequate credit rating.

- A sukuk whose underlying funding arrangement is based on ijara will necessarily require the Obligor to have at its disposal suitable (halal) income-producing assets on which to base the transaction. In addition, unless the correct mechanics are included within the documentation, the substitution of similar assets into and out of the structure would be impossible. This could limit the Obligor’s ability to sell or deal with the asset during the life of the transaction.

- Unlike the conventional bond market, the standardisation of documents for sukuk issuance has been slow to develop, and this can have adverse cost implications.

- From transaction to transaction – depending on the extent to which the structure used for the sukuk departs from the typical structures already well recognised in the market – the involvement of Sharia scholars is necessarily required. This can add some additional cost as well as an element of unpredictability to the transaction structuring process.

- As Sharia scholars may have differing views as to how compliant any given structure may be, there is no absolute unified and settled body of opinion on these issues.

- The tax treatment of sukuk may be dissimilar to conventional bonds in certain jurisdictions.